return to 2004 Choosing a Subject

by Miles Mathis

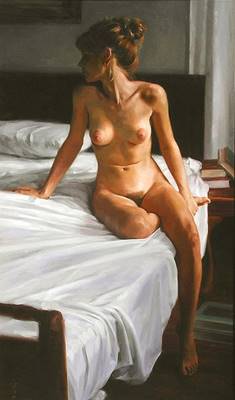

The naked woman's body

is a portion of eternity

too great for the eye of man.

William Blake

The Impressionists are famous for, among other things, popularizing the belief that, it's not what you paint, but how you paint it. John Sargent, in his "impressionist phase"—while painting at Broadway, in Worchestershire, England, in the 1880's—also became known for his arbitrariness in choosing a subject. He explained that he wanted to "acquire the habit of reproducing precisely whatever met his vision without the slightest previous 'arrangement' of detail, the painter's business being not to pick and choose, but to render the effect before him, whatever it might be."

Despite my indebtedness to Sargent, I could not possibly disagree more. The painter's business is to pick and choose, lest art become the equivalent of the random snapshot. How does an artist share the mood, personality, and expressiveness, not only of his subject, but of himself, except by the choice of subject matter and how to paint it? The line, color, composition and mood of a subject, human or not, must speak to the artist, must interest him in their potential for expression, and must inspire him to express himself through them. And so the choice of subject matter becomes the most important decision the artist can make. An artist may practice on random subjects, but he or she cannot hope to produce art randomly.

What an artist chooses to paint says a great deal about what that artist wants to communicate. Renouncing this choice is simply to empty a painting of a large part of its potential for expression and to encourage the viewer to judge a work on its technical merits alone. But a work of art, properly so called, is not just beautiful or interesting paint. It must be judged as a painting, and as such must carry some quality beyond technical virtuosity. Your choice of subject matter will determine, in large part, what quality it will have.

There are as many different forms of artistic expression as there are expressive artists, but I only know of one well enough to write about it: that being, of course, my own. In this article I hope to clarify the importance of choosing a subject by showing how and why I pick a model, a pose, a composition, and a technique that will express what I have in mind (as far as what I have in mind is conscious, and allows for a rational explanation).

To start with, as a figure painter, I can't overemphasize the importance of hand-picking your models. Anonymous art-class models won't do. Nor will advertising in the paper. The chance of attracting really interesting models that way are almost nil. In order to discover exactly what your inspiration might be, you must give yourself the freedom to choose what you want to paint, not what is offered you, or what is available, or what the fashion magazines tell you is beautiful, or what the market asks you to supply. None of this is art. Art is only that which comes from your desire, your need. This is not to say that you should idealize your art, changing your models to fit some pre-conceived notion. It is not to say that you concoct an idea of perfection in your head and then go in search of someone to match it. It is to say only that you must choose for yourself the subjects that interest you. Only in this way can you personalize your treatment of the subject without developing conscious mannerisms. Your works should be recognizable as yours because they express the individuality of your mind, not because they exhibit eye-catching surface characteristics chosen for their salability.

To find this inspiration, you must simply keep your eyes open wherever you go—to the grocery store, the theatre, the library, the swimming pool—and develop the courage to approach the people whom you find interesting. Be calm (not cool) and trusting, and people will trust you, especially if you have a portfolio with you at all times to prove your intentions and your seriousness. But do not confuse seriousness with being "all business". Make friends, get to know your models—art is not impersonal.

I do not want to give the false impression, though, that is so easy. You will probably not find many good models, and I don't want you to think that there is anyone who paints the figure in this day and age who avoids great disappointment and, often, tragic misunderstanding. Perhaps the most discouraging thing one may encounter in a person who otherwise appears polite and intelligent is a mind that is completely closed to anything the least bit out of the ordinary. Artists have become such a fringe element, in the worst possible sense of the word, that no one, not even street people, trusts them. We are only a half-step above lawyers; but at least most people have an idea of what lawyers do. The appellation "artist" brings up dozens of cloudy images in the mind of your average citizen, most of them bad if not outright criminal. These images are incomplete—based on a daily diet of sordid news and a spotty (and often equally sordid) knowledge of art history—but they are too often based on fact, sad to say. For example there is the "artist," usually a photographer, who uses his job or hobby as an excuse for meeting women. Let me be clear here: I do not want to be a hypocrite. There is nothing wrong with developing personal relationships with those with whom you work, relationships of friendship or love. The idea that such a development is semi-taboo or unnatural is ridiculous. If we can't find our friends and lovers through our work, which in the modern world takes up so much of our time, we will be even lonelier than we already are. But so-called "artists" who use art only or predominately as a front for sexual conquest are reprehensible, not only for how they generally treat those with whom they work, but for how wary they force potential models to be. A model who has a bad experience with such a poseur will at least have an excuse for her skittishness. Only an excuse, mind you, for there is no good reason for anyone not to give other people the benefit of the doubt in a protected situation, no matter what they've been through (I say protected because I have never approached a model in a dark alley or in a deserted subway car). In my opinion, people who have allowed themselves to become so jaded that they cannot even entertain the possibility of an honest, enriching encounter, might as well put bullets though their heads. Because, it must be said, they will never again have such an encounter.

Another image that pops into people's heads when they hear the word "artist" is that of the Modern paint splatterer or giant-canvas attacker or rusty-metal welder or found-object construction-piece performance-art juggler. It is understandable that a beautiful, intelligent, honest young woman might not see her role in such an art, and question the motive for her desired presence.

Then there is the graphic "artist" or fashion designer or advertiser who needs all the pulchritude in the world to sell his shoddy and likely useless product. The only thing that lures the pulchritudinous to such fields is the huge hourly wages they offer. But no one who is not pursuing "professional" modeling wants to have anything to do with these advertisers.

And finally, the actual pornographers themselves, the generators of a billion-dollar business (according to an estimate I heard on NPR), no doubt refer to themselves, when propositioning models, as "artists." It is no wonder that those we approach are wary.

All this just goes to say that the Ted Bundys and the Jeffrey Dahmers of the world, as well as the multitudes of less-dangerous perverts and money-grubbing phonies make doing anything genuine and good very difficult. Your existence as a true artist and craftsman, with honest emotions, high goals, and real principles, will be not only doubted but resisted. This is one of the facts you will have to accept and overcome. Many artists have been driven back into the house and under the bed upon this discovery: that not only the galleries and buyers, the critics and academics, the museums and the NEA have forgotten what art is about; Mom and Dad and the girl next door have forgotten, too (or, actually, never knew). Mom and Dad, if they can find the time, may pose for you just to be nice (or because they still want to believe, beyond all hope, that despite the fact that you paint nudes you may be able to avoid becoming a sexual deviant or child molester; and because you are painting them you are not painting those deplorable nudes—which are hopefully just a phase). But the girl next door is not family, is not so biased in your favor. It would probably take less pleading and convincing to actually get her into bed than to accept, or care, that you have real artistic talents and goals.

Even if you put together a portfolio and resume that would be the envy of the Renaissance Masters, your problems will remain, for only the Renaissance Masters will know its value. The young model you are so excited about will not know what any of it means. If it were fashion photography or even pornography, she might be able to judge its quality; for it is more likely that she has seen these things than that she has seen good figure painting. As for your resume, you might as well save the paper for sketching. The resume of an economist or stockbroker or radiologist might impress someone. But who today could even read the resume of an artist. Besides, if your portfolio cannot be understood, what chance is there that your resume will fare better? In the end all you can do is beat the bush and hope to flush the occasional rare bird. For the model, like the client or gallery owner, who is truly interested in art is rare indeed.

Once you have found such a model (and you will, you will, fidus Achates) all the rest becomes easier. You will be working with a natural, as opposed to a professional model, so you don't have to worry about insipid stock poses, disingenuous glamour looks, or other pre-conceived notions. To keep this freshness and ingenuousness, you yourself must resist approaching the session with any hard and fast ideas about what you want from it. At first your model will be nervous and stiff, but if you just let her be, if you let her move around freely, without restraint, without a lot of "artistic" ideas or intentions in her head (or yours), the pose will come. You will not make it come, you will discover it, just by watching. See what she does that is unique. Wait for the moment that says something about her, about you, about your relationship, and seize it. Try to capture something of it on canvas. That is all you can hope to do. Or that is all I can hope to do. Even at my best, I have found the task mostly beyond me. Whistler believed that art could surpass nature, that "The Gods stand by and marvel, and perceive how far away more beautiful is the Venus of Melos than their own Eve." I'm afraid I can't concur. I've only been able to approach the beauty of the people I've known—the power of art, even of the greatest masterpiece, is always only fragmentary and partial. The beauty of living flesh cannot be equalled, much less surpassed.

To some this method of choosing a pose, by simply watching, may seem passive (especially for someone who just accused Sargent of being arbitrary). But Rodin, who kept nude models in his studio at all times even when they weren't posing for a particular sculpture (because he liked being constantly reminded of the possibilities and surrounded by spontaneous inspiration), was once accused of letting the models give him orders, instead of the other way around. He replied, "I do not take orders from them but rather from Nature." He meant, of course, not only nature as an external force, but also his own nature. Life spoke both to him and through him. And so this method is anything but passive. It is active without being manipulative. It allows the subconscious to make its choices without the interference of reason.

Pascal said, "The heart has its reasons which Reason cannot know." There are times when analysis, the interference of reason, or of the left brain, is simply counterproductive. For if anything must be kept in mind it is that the intelligent artist must guard against over-refining his work. Perfect work is uninteresting work, for perfection is not human. Look at the work of Rembrandt or Goya or Chardin or Corot—their imperfections are as necessary, as beautiful, as their perfections. As Heinrich Heine said, "As in life, so in art/ The greatest good is grace."

What this means to you, day by day, is that when you are painting you should lay in some areas quickly, spontaneously, and then just let them be. Don't feel like you have to work the whole surface over and over till it glows. Allow for some variation. Some areas may look best scratched in with just a turpentine wash or a thin layer of paint. Other places may need to be built up painstakingly with multiple layers, impasto, or glazes. The point is to paint with no preconceptions. Don't go in thinking, "I'm an Impressionist, I have to paint everything loose and thick and bright," or, "I love this photograph and I'm going to copy it down to the tiniest detail." Go in thinking only, "This subject has something to say to me, and I to it, and whatever I have to do, I will do."

Avoid all formulas. Avoid, even, consciously developing "a style of your own". A style of this sort is a marketing trick, and has nothing to do with art. In fact, it is a barrier to art, because it limits the creative possibilities at the very beginning of a work. Technique must always remain a means to an end. You must always control your tools, including your style, rather than let them control you. The painter who limits himself by choosing a "signature style," an immediately recognizable palette, or brushstroke, or subject, will become an ally to the gallery owner and buyer, but will never develop beyond a very narrow set of boundaries. This is because he has indicated by his choices that he is a businessman, not an artist. But a real artist makes artistic decisions, such as choice of subject matter, color, or brushstroke, based on artistic considerations, not on material considerations. This is what it means to be an artist. The rest are just businesspeople who happen to deal in the production of pictures.

As you mature as an artist, you will find that certain

things work for you, and these things will show up more or less often in your

work, naturally defining your style.

The question to ask is "how do they work for you?" If they work to allow you to express yourself,

fine. But if they work as shortcuts to

help you work faster, or if they work as formulas to help you work without

having to think, or of they work as eye-catchers to help you sell paintings,

they need to be resisted. You can be

sure that none of the great artists of the past allowed themselves to be

defined by the market or by the clock.

The great masters, like Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh, were

great because of how they thought about their work. Their standards were incredibly high and they disdained

compromise. They painted or sculpted to

produce great paintings or sculpture.

Everything else was secondary.

Such single-mindedness would be considered monomania these days, but it

remains the only way to stay the course.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.