return to 2004

On Jenny Saville

by Miles Mathis

L'ideal a cessť, le lyrique a tari.—Saint-Beuve

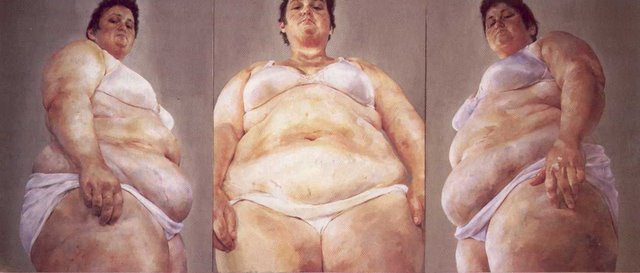

I read a piece on Jenny Saville in ARTnews in November and have been waiting for the opportunity to comment on it. Now is my chance, I suppose. Saville, along with Currin and Fischl and a handful of others, is one of the few figurative painters to make it big in the last couple of decades. She was one of the early discoveries of Saatchi Gallery, London—that prince of promoters—and she has since ridden the wave of feminist commentary on the body that has become a staple of modern politics and political art. Technically she does have some talent, but that is not what has made headlines for her. It is her content that has made her so appealing to a certain sort of viewer.

In the eyes of her supporters she is a crusader, brutally honest and unflinching in the presence of hard truths. In the article we are told, "She describes the subjects of her work as 'images of extreme humanness,' even in the case of her recent images of emotional and physical pain and violence...."

Where does this pain and violence come from? Why is Saville, who grew up a normal middle-class girl in Scotland, who had encouragement from her family to be an artist, who went to the Glasgow School of Art, who travelled through Europe as a girl to look at art, who had art books and lessons and role models, why is she so full of pain and violence? According to the article it is because her artistic role models were men. Sargent, Rembrandt, Soutine, de Kooning. All men. Horrible.

She escaped from this nightmare by discovering the writings of Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous and Luce Irigaray, who "maintain that cultural standards in Western society remain largely phallocentric." We are to understand that this explains why she should want to paint Woman as scarred victim, as bloated peeling object, as giant mass of angst-ridden blubber.

Possibly the most informative quote in the piece is this: "I'm more fascinated by the stories that imprint themselves on the body. Whether its a fat, injured, or scarred body, it has undergone a journey to get there."

Has it? Many many miles back and forth to the refrigerator? That harrowing car ride across town for rhinoplasty and lipo?

I'm sorry, I can't even take all this seriously anymore. The political transparency of articles like this, the absurd levels of pathos, the fake seriousness of it all preclude my even pretending to sympathize.

God knows we all have problems—the world can be a horrible place, even for those of us living in the "sanitized first world". We were picked on as children and are misunderstood as adults. We don't have enough friends and lovers, our governments are wholesale failures of one sort or another, and everything we touch is poisoned. And I am very sorry that Saville was a fat girl who didn't get asked to the prom or whatever. But none of this is an excuse for her art.

The title of the article is The Body Unbeautiful. This is supposed to imply some sort of emotional depth that The Body Beautiful could never match. Saville says so herself. Ugliness is itself a sign of distinction. It is the sign of a journey.

Balderdash. If beauty is only skin deep, so is ugliness. In which case it does not mean anything like what Saville intends. She wants to make herself into a martyr. But she is not a martyr: she is just another young woman made sick by her victimhood. She has found no subject greater than her own emotional turmoil, much of it manufactured by these women she is reading. Make no mistake, I am a far-left liberal in most aspects, in favor of fair treatment in all ways. But I simply do not buy the argument that this is still about equality. I don't buy the argument that women in the US and Europe are suffering great institutional cruelty at the hands of men. No more than men are suffering at the hands of women. That "phallocentric" adjective offends me, as a progressive. It is just a shibboleth. It is a rallying standard for women with a grudge; women who want superiority. The US and Great Britain are now so far from being phallocentric it isn't even worth breath responding to.

Besides, Saville's art isn't really about any of that. That is just the pretext for her particular pathology. She admits that she went to the these writers seeking justification for her art. And she found it, no surprise there. Her fascination for ugliness predated her acquaintance with the feminist justification of it. It is interesting to note that Lucian Freud had no need for a masculist justification for his analogous fascination with ugliness. He just likes ugly. Modernism justified his pathology for him after the fact, and Saville benefits from a double justification: both modernism and feminism like ugly. It happens to fit in with their deconstructive tendencies.

But is there really any depth there, political or otherwise? I don't think so. The political depth of Saville's art goes precisely as deep as would the art of a bald man "speaking for all bald men and the terrors they have endured." Go back to her "extreme humanness" quote. Are ugly, scarred, fat people really more human than other people? Let's flip that over and see how it looks. What if I said, "I paint beautiful people because they are more human. Their beauty means to me that they have probably done more interesting things, and are basically superior." You would think I was bonkers. But Saville's quote, although just as bonkers, is politically correct. It is allowable.

And Saville's politics is not even consistent, as I see it. If she is selling the feminist party line that all the media wants is skinny girls with high cheekbones, then she should be pushing the counterpoint: beauty comes in many shapes and sizes, and all that. Rubens and Renoir found a way to paint fat women with love and tenderness. But Saville's women are made to look their worst. She uses her broken facture to make the skin as repellent as possible. Saville seems to imply that women have the right not only to be fat, they have the right not to wash their hair or cut their toenails, and the right to wear underwear six sizes too small. If men have a problem with this, it is further proof of their shallowness.

What makes it all even more distasteful is that Jenny is painting herself as the ugly, scarred one, meaning, by her translation, the one who has been on the interesting journey (as opposed to those pretty, empty people). It is art as self-promotion, as self-exegesis, as therapy, as exhibitionism, as diary. It is the sad cry "look at me—I am interesting even though I am fat. In fact, I am interesting because I am disgusting." I don't buy it. People are no more interesting because they are disgusting than they are interesting because they are not disgusting. To interest me, either as an artist or a dinner companion, you have to do more than look really bad (or good).

I am not interested in seeing a male or a female artist post either their own beauty or their own ugliness on the world as a sign of spirituality. I am not interested in seeing any sort of transcendent victimhood. The only reason the world has put up with Van Gogh's pathology is that he had no idea he was exhibiting it, and because it is so self-effacing and naive. And because some of the paintings are fantastic regardless. But as a rule pathology makes poor art. Especially when it is self-centered and manufactured. This is what the moderns have not understood.

I look forward to the day when women finally come out above all this negative feeling and begin to feel good about themselves physically. That is the last equal right, one they have not given themselves. I am certainly not keeping them from it. I would love to see more beautiful paintings of women by women. And to make the equality even tighter, I would love to see more beautiful paintings of men by women. In this last case, I don't think we would complain of being treated as objects—we would understand that we were loved.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.