return to homepage

return to 2003

Note:

this is the second of a three-part series of articles published in Art

Collector/Art Connoisseur magazine in 1999.

Art in the Past

by Miles Mathis

In my last

essay I closed with the assertion that the art connoisseur may recognize

genuine art "by the good it does him." This rather broad statement

demands refinement. Probably no

subject in art has caused more contention, or generated more opinions, than

this one. And rightly, for it is

central to the definition of art. The

questions What good does art do? or What is art good for? both

lead to the question What is the proper content of art?

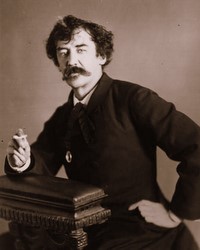

The painter James Whistler and the poet

Algernon Swinburne*, once friends and collaborators in art, parted ways over

this very question. In his famous

"Ten O'Clock Lecture," Whistler claimed that art purposed "in

no way to better others," that art had "no desire to teach."

It

is indeed high time that we cast aside the weary weight of responsibilty and

co-partnership, and know that, in no way do our virtues minister to [art's]

worth, in no way do our vices impede its triumph!

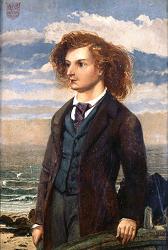

Swinburne

disagreed. He noted, specifically, Whistler's portraits of his mother and of

Thomas Carlyle as appealing to "the intelligence and the emotions, to

the mind and the heart of the spectator." Swinburne, who did not share Whistler's taste for Japanese art,

argued that great art required more than a pleasing form:

Japanese

art is not merely the incomparable achievement of certain harmonies in color;

it is the negation, the immolation, the annihilation of everything else.

Art requires

content, he implied, and any enriching or ennobling content, no matter how

circumstantial or uncontrived, might be called moral. Whistler complained of

an aggressive misreading and publicly broke off the friendship. But between

the agenda of Whistler and that of Swinburne may reside an artistic constant,

and it is in this gap where we should look for their reconciliation 111 years

later.

First,

though, a few other historical opinions on what good art might do. For

Charles Baudelaire (a contemporary of Whistler and Swinburne) beauty in art

is not what is pleasing to the eye, but what is pleasing to the spirit.

Baudelaire knew first hand the latitude of the spirit—how far it might stray

from the good and the beautiful, and yet inform itself. Baudelaire influenced

Rodin, who put it this way when speaking of his The Helmet Maker's

Beautiful Wife (which was not beautiful): "There is only one beauty,

the beauty of truth revealing itself."

For others

in the late 19th century, truth was never the realm of art. For artists as

different as Puvis de Chavannes and Van Gogh, art was the painted dream, a

transcendence of "real" life, a personal place of redemption for

existing absurdities. Vincent, to be sure, loved Millet and his peasants,

even preached an early form of solidarity. But well before his seizures it

was already clear that he would never consider art to be a sermon. His

painting did not cry out for the dispossessed, rather it connected them to a

perceived order: the swirling stars, the curling fruit trees, the muddy

brogans made insignificant the propaganda of the "possessed." This

order might be linked to the order sought by El Greco, Michelangelo, and the

Greeks (whose idealizations concerned their own painted dreams). Even Rodin's

"truth" is closer to this idea of order than it is to any social or

political reality. Remember, he chose to mold the Gates of Hell, not the

doors of the Republic. It also has much in common with the transcendentalism

of Carlyle and Thoreau: Van Gogh was in search not of a political solution,

but of a spiritual one. And it is also linked to Nietzsche, who went insane

in the same year as Van Gogh. Both believed in an aesthetic justification of

the world. Vincent never would have thought of art as politics; Nietzsche

thought of it, and considered nothing more contemptible.

The idea of order was mostly jettisoned in the early 20th century, as all

faith, pagan as well as Christian, dissipated. Existentialism was born, and

temporal questions became all-important. Art as diminishing form and art as

politics have battled it out: politics has won, but minimalism and

deconstruction have also left a deep mark. The pre-modern virtues in

art—beauty, subtlety, elevation, craftsmanship—have suffered a setback

unknown since the dark ages. And order has been replaced by relevance.

In some cases, politics was the cause, formalism the tool. Clement Greenberg,

most famous for espousing the greatness of Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman,

was seen to be continuing Whistler's argument for purity. Greenberg and

Whistler have both been called formalists, jettisoning all thematic content.

But Greenberg argued far beyond Swinburne's conception of Japanese art—he

desired the immolation of all content (including beauty) and the distillation

of painting into a sort of "absolute." Hence Newman's gigantic

monotone canvases with, perhaps, a single line.

Much art and

criticism since the 1960's has argued the opposite. Content is everything,

form nothing. This is why painting and sculpture are rarely taught anymore.

Beuys, following Duchamp, made art into a political or philosophical action,

an action that may or may not require the production of a "thing,"

an artifact. Artists in this camp argue for content while turning Baudelaire

and Rodin on their heads. Art must be displeasing to both eye and spirit,

otherwise it has no power to change.

In the 20th

century, form and content have affected a complete separation.

Form-without-content is now mostly passe, because it is less in need of

criticism. Content-without-form remains ascendant within the avant-garde; and

the antics of Bruce Naumann or Damien Hirst are promoted because they advance

the deconstructivist agenda. For the critics, any form is now as good as any

other, and even figurative painting is re-accepted as long as it conforms to

the requirement for social commentary, if not subversion (think of Lucian

Freud or Francis Bacon).

But the

reconciliation of Whistler and Swinburne might also be, in many ways, the

reconciliation of these two main branches of Modernism. Art is the necessary

conjunction of form and content, and Whistler knew this all along. Whistler

was no formalist. It was not content in general that he wished to dispense

with, it was literary content. He said:

Apart

from a few technical terms, for the display of which he [the critic] finds an

occasion, the work is considered absolutely from a literary point of view;

indeed, from what other can he consider it? And in his essays he deals with

it as with a novel, a history, or an anecdote.

Substitute

"political" for "literary" in this quote and it is

updated for our time. Many will ask, once political and literary content are

dismissed, what is left? Psychologism? Self-indulgent murmurings? Emotional

hiccups? Whistler was fond of musical analogies, and he might ask, once such

content is dismissed from music, what do you have? The answer? Music! Is

Debussy "self-indulgent murmurings"? Is Mozart

"psychologism"? Were Bach's Cantatas just "emotional

hiccups"? Or, more to the point, is Michelangelo's David,

stripped of his biblical and Florentine content, just a naked boy? The

perverted wish fulfillment of the artist's mind? Is Starry Night just

the product of too much absinthe? There are many in the upper echelons of art

who would say so: the ones who are so au courant that they are past the

naivete of being "done good" by art. Yet it is just this sort of

good that art is fitted for: not agitprop or allegory, but the otherwise

formless conviction that we are not all, or always, "A little, wretched,

despicable creature; a worm, a mere nothing, and less than nothing."

*Swinburne

wrote a poem, Before the Mirror, for Whistler's painting Symphony

in White no. 2—the poem was mounted on the frame of the painting for its

first showing in 1865.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.