|

return to 2003

An

Artist on the Left:

a

Variation on a Theme by Whistler

by

Miles Mathis

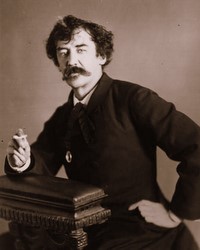

The Victorian artist

James Whistler—most famous in America for the portrait of his

mother—published in 1890 a collection of essays and letters to

the editor entitled The Gentle

Art of Making Enemies. It is now

little known and hard to find. Despite that it remains one of the

most important artist-produced literary documents in history.

Leonardo's Codex,

Blake's poems, and Van Gogh's letters may be the three greatest

written artifacts produced by painters; but the Gentle

Art is the single most

significant counter-critique in history, for it alone confronts

the problem of art theory and art criticism from the point of

view of the artist.

my

personal copy, first edition from 1890

Few other artists have bothered to write or publish in defense of

themselves or of art in general. Until the time of Whistler, it

was simply not necessary. Historically, it had been the case that

pulchrum est paucorum—that

is, art was for the few. Artists had to answer to the clients,

the kings and popes, the aristocracy and the clergy. But only to

the clients. Art was a compromise between artist and patron, a

dialogue limited to two voices.

We all have read of the authority of these patrons, especially

when the patron really was the King or Pope. But it should be

clear to anyone who has read history that the artist often had

great authority as well. Michelangelo may be the clearest

example. Many modern critics have accused Renaissance artists of

being the political operatives of the aristocracy. Michelangelo,

we are assured, was a pawn of the Medicis. But the historical

record contradicts this. The Medicis enabled Michelangelo; they

never defined him. Michelangelo was the Van Gogh of the 16th

century: difficult, stubborn, temperamental, even monomaniacal.

He fought with the various Medicis and Popes (including the

irascible and domineering Julius) and won. The Sistine Ceiling

was Michelangelo's conception, not Julius'. The David was

Michelangelo's idea, not the Florentine Signory's. By today's

standards, Michelangelo had almost unheard of power and freedom.

Of course, in hindsight, he appears hemmed in by the subject

matter of Christianity and Classicism, but he would not have felt

this. He was a Christian by choice, not at the point of a sword

or at the dangling of a gold coin. He respected and loved the

Greeks and their sculpture not because he was psychologically

compelled to—by fashion or fascism—but because the Greeks

were worthy of his respect. No matter what 20th century criticism

tries to make of Michelangelo, he will remain the primary figure

of 16th century art; not Julius or Alexander VI or the Medicis.

This balance of power—that

tilted toward the artist in the case of Michelangelo or Leonardo

or Titian or Rembrandt (or, admittedly, toward the patron in the

case of many lesser artists)—began to be complicated by other

interests at the end of the 18th century. Denis Diderot became

the first world-famous art critic when he began reviewing the

Paris Salons during the reign of Louis XV. His newsletters were

published privately, and went out only to the aristocracy across

Europe, but the die had been cast. No longer was art simply a

transaction between artist and client. No longer was the buyer

the only one whose "taste" must be taken into account.

As the Salons became more and

more popular over the next century, and as a greater and greater

percentage of the population became wealthy enough to buy (or at

least free enough to look at) art, more and more people became

necessary to the administration of this art. A large number of

art writers were hired to inform the market—and the

public—about art and art theory in the ever-expanding journals

of the day. At first many of these writers were as well-qualified

to critique paintings as a non-painter could be: they were

writers of poetry or fiction—creative people in their own right

who understood the mystery of creation. In the mid-19th century,

Baudelaire was a prominent critic, for instance. And after him,

Zola. But already the demand for ink was outrunning the supply of

qualified pens. The artists were busy painting, and either

couldn't write well or didn't care to.

The great writers soon recognized how foolish it was to act as an

authority in another's field of expertise. Painting was not

literature, and could not be critiqued as literature. This left a

hole; and, as we know, nature and the media both abhor a vacuum.

Fortunately for the magazines there was no dearth of other

writers willing to expound on any subject, no matter how far from

home, no matter how high or low. Men who had been thrown out of

the Ecole, denied by the Academy, scorned by the colleges; men

who had never tried to draw; color-blind men (I am not making

this up): all lined up to scribble for the cheapsheets.

This is where Whistler entered the fray. He wrote his first

letter to the editor in 1862. He complained to the Athenaeum,

London, that his painting "Symphony in White, no. 2",

was not entitled "Woman in White," and that it had no

relation to Wilkie Collins' famous novel of that name. He wanted

it understood that his art had no literary references and

required no literary references.

In his long career he wrote many such letters, correcting the

misconceptions of the public and the critics about his art and

about art theory in general. These letters are some of the

crispest, tersest, most brilliant repostes in the history of

polemics, and I recommend them to anyone with an interest in art

or argumentation. But Whistler also wrote a small number of

treatises, and delivered one of these at his notorious Ten

O'Clock Lecture. In all of them

he expertly attacked the presumptions of the critics and their

purposeful misleading of the public. Finally, in 1877, Whistler

sued the famous art critic John Ruskin for libel. He was awarded

only a farthing (less than a penny), but the stress of the trial

destroyed Ruskin and he never wrote criticism again.

Whistler's

success in the battle to define art was the last victory on the

side of the artists. The entire 20th century lies squarely in the

column of the critics. Kandinsky is the only well-known 20th

century artist who made an attempt to argue with criticism, and

he was unsuccessful. Neither his art nor his arguments were as

strong as Whistler's, and he was anyway outnumbered. By the late

teens and twenties Picasso's PR successes had made any genuine

statement of fact irrelevant. Picasso had made allies of all the

enemies, and battle on the old terms was no longer possible. The

circle had closed, and the artist with scruples was outside the

circle. If the critic postulated it and the artist (Picasso)

verified it and the patron bought it, then art was complete.

Nothing else was necessary.

Art has existed by this definition ever since.

Duchamp was the first to fully understand what it took much of

the 20th century to finalize: in the above equation of critic,

artist and patron, the artifact is absolutely superfluous. If you

have a theory, and an "artistic" verification of that

theory, and a sale, you have a market—a market you are as free

to call "art" as the next salesman. "Artistic

verification" can be anything. A discarded commode. A bubble

on the bottom of the sea. The idea

of a bubble on the bottom of the sea. Anything. Art since Duchamp

has been a puerile list of absurdities. Somehow we have spun out

almost 90 years of fascination with this game. Duchamp's only

virtue was to get bored with it rather quickly and resort to a

thrilling life of chess.

By

around 1980 even some of the critics were getting tired of the

game. Robert Hughes—Time's

art critic since 1970 and a great apologist for Modernism—felt

it was all over by the early 80's. But where every head of the

hydra was cut off (or got some sense) two more sprang up. The

market was too lucrative to let go without a fight. If the

critics lost interest, the museums and galleries could find new

critics. And they did. And they learned from the financial crises

of the 80's, and the political crises too. They learned to

diversify: to allow a wider range of styles back into art—as

long as the stylists still agreed to be subordinate to Theory.

They called this "Pluralism." It appealed to America's

sense of fairness and equal opportunity—without really

addressing either one—and so was perfect. The art dealers and

administrators learned from the political candidates how to

manipulate public opinion—how to mouthe the proper catchwords

at the proper time. Publicly displaying absurdities and inanities

became an issue of "free speech." Those who expressed a

desire for real art in our contemporary museums were no longer

browbeaten with elitist terms like "bourgeois" or

"anti-intellectual" or "unrealized" (as they

might have been in the 70's). They were now accused of

"censorship" and "fascism." They had gone

beyond stupid. They were now evil. Un-American.

Recognizing that almost all residual public support for art came

from the left, the avant garde began labelling all opposition as

right-wing extremists. This effectively silenced all progressives

who might wish for something else from art. No one on the left

wanted to be lumped with Helms and Giuliani.

In the press

the road is now described as having only two forks: hard right or

hard left. That is, we either take what we have, and like it, or

we underwrite Neo-Nazi "propaganda" art—that

glorifies the state and embellishes the rich. The obvious fact

that the road can go anywhere we want to take it is purposefully

obscured by art critics. As is the irony of the situation: the

avant garde is now the status quo.

Nor does the right disagree with this presentation of the

situation. The Wall Street

Journal and ARTnews

see the battle in precisely the same terms. The right has

accepted the delineations of the left, and only disagrees with

its "taste." Meaning that the right, like the left, is

as far away as possible from any idea of artistic autonomy. The

right is fine with the politicization of art—it just wants a

right spin rather than a left spin.

This puts us in a

unique situation art-historically. We have an entrenched

institution (Modernism) but almost no opposition. Historically,

opposition to entrenched institutions have come from "below."

That is, the institutions were aristocratic or plutocratic, and

the revolutionary spirit resided in a more democratic

"under-class." Certainly that has been the movement

since Impressionism. Now, though, there is no "under-class"

left. The avant garde has cleverly positioned itself on the

bottom of the sea, and no one can get beneath it. Any opposition

from "above" can be shouted down as elitist, no matter

how far left it comes from. Even Ralph Nader and Noam Chomsky can

be dismissed as aristocrats when they start questioning avant

garde art.

The only

intellectual critique of the avant garde that I have seen

published in the mainstream in the last forty years is by Tom

Wolfe (I disregard all moral or religious critique from the far

right as being outside my argument, here). I mention this neither

to praise nor to bury Mr. Wolfe: I mention it because it is a

strange statistic in a "free society." I can't imagine

that the opposition to avant garde art from the left and the

center is so small that it may be represented by one man over

that period of time. I suspect that lessons were learned by

writers in the sixties and seventies, and that these lessons

weren't all about "freedom." I suspect that Mr. Wolfe

is the only one who has had the necessary skills to have survived

his opinions.

This only goes to show that there is no

true dialogue. Art has reached a point of non-correctability, a

sort of stretched out "now" with no future. A recycling

of stances and poses, with a subtle change of shoes. Art theory

is now like a math theory: one that allows for infinite spreading

along the x-axis, but no movement at all along the y-axis. We may

go as far afield as we like, that is, but may not climb.

The avant garde owns the museums, the universities, the critics,

the NEA (what is left of it), the magazines. It chants

"Pluralism" at the same time that it viciously attacks

any theoretical dissent and ostracizes any artist who will not

capitulate. The artist's confidence has become so enfeebled, so

devitalized, by a century of psychological strafing that it

cannot imagine existing without the life-support system sold by

the institutions. And in the rare case where an artist crawls

from the ooze with his pen, or massages his larynx and prepares a

fateful "yop," he finds the audience elsewhere:

listening to a curator at MOMA lecture on the proper subject

matter—or the exact philosophical stance—for the artist. Or

reading the latest press junket from the priests of PoMo at

ARTnews

or The Nation.

The truth is, art is not a political category. It is not

the property or the tool of the left or of the right. It is

neither elitist nor egalitarian. It is personal. It is the gift

from the individual to the group, and does not empower anyone.

But it can only flourish in the group if it has bi-partisan

support. It requires the goodwill, and the freedom from undue

influence, from both sides. Currently it has it from neither, but

its greater enemy is on the left. This is simply because the left

owns art. By the accepted definitions, what the right likes is no

longer called art. It is called kitsch or pastiche or decoration

or whatnot. But it is not even considered a contender for

contemporary art history books. It does not make it into the top

museums or the top galleries. The upper financial echelons of

contemporary art are exclusively the territory of modernism and

postmodernism. No living artist that is accepted by the right is

getting millions for a painting. Andrew Wyeth comes close, but he

is the only exception. Even the mainstream, bipartisan magazines

and newspapers, like Time,

Newsweek,

and The New York Times,

do not report on the art preferred by the right (as well as by

many others across the political spectrum). The

Wall Street Journal very rarely

carries a piece on the non avant garde, but even then, the tone

is almost always derogatory.

I

mention this not to defend the right or the art it prefers. I

mention it as proof that most of the pressure on artists to

conform to current fashion and policy is from the left. A young

artist, no matter how progressive politically, does not need to

attack the Republican party or the right because the right has no

power in art. An artist does not need to watch his right flank

because he is in no danger of being chewed up by conservative

zealots. Conservative zealots have nothing to do with the current

definition of art. They occasionally complain about its worst

excesses, but this is a only a negative power of a very small

sort—exceedingly small because they almost never win. They are

still losing each and every PR battle.

It is the artist's left flank that is under constant pressure and

constant attack. The list of tabooed subjects, moods, treatments,

motifs, and genres is endless, although few things on this list

would seem to have an immediate interest to the left. As I list

some of these taboos, keep in mind that this all falls under the

rubric of Pluralism—where "everything is allowed."

Everything except. . . .

Let's start with beauty. Beauty

is not only disallowed, it is not admitted to exist. It is

considered a social construct of the flimsiest sort, existing

only subjectively and only as a tool of a shallow and oppressive

mindset. According to the most progressive theories, it was

constructed by men who used its existence to justify the

domination of both nature and woman. In this view, a landscape

and a nude are equally sexist and offensive, unless and until

they have been drained of all beauty. Only then may they

transcend the error of treating the world as an abject object. If

you wish to learn more about the intricacies and background of

this theory, I recommend you to the writings of Jacques Lacan.

The proponents of this theory

do not attempt to explain how an unbeautiful landscape or nude

is, philosophically, less of an object than a beautiful one, or

what failing to be attracted to the world is supposed to teach us

about the rights of the oppressed or any other deeper meanings or

values; but the theory is a clever tool for demonizing the male

Id, and it has been quite successful in stamping out the sort of

"shallow" creativity exhibited by men from Michelangelo

to Rodin, Titian to Van Gogh. . . and even Picasso.

Health is also forbidden. Partly this is due to its connection to

beauty. But there is more to it than that. A healthy painting is

thought to be necessarily insincere. This is not a healthy age;

therefore, any depiction of health or vigor is false. Health also

lacks psychological depth. We learn from our sorrows in this vale

of tears, and only the ignorant are healthy.

Children or animals should not be depicted unless they are being,

or have been, brutalized in some way. This taboo ties into the

one above. No social critique can be spun from happy children or

unterrorized animals.

As you

can see from the three taboos already listed, the figure is

almost universally disallowed. There are a few exceptions.

Corpses, scary dolls, and the terribly disfigured or malformed

are encouraged. They are obviously relevant to our political

situation. Very ugly people—the grossly corpulent, sick,

wasted, insane, addicted may be depicted if it is clear that they

are poster-people. They are examples (do not confuse examples

with ideals). "Normal" people may be depicted only if

they are hated by the left. Businessmen looking like predators,

politicians buggering eachother—these are OK. But even if you

voted for Ralph Nader (even if you're a communist and a Buddhist)

you may not paint a picture of your wife. Unless she has cancer,

or she has decided to eat your children.

Skill is disallowed. You may paint corpses, but you should not

use too much technique if you do. If you paint corpses with very

much finesse, you will make artists who only paint stick-figure

corpses feel bad. Also, someone in an unguarded moment might say

your paint was beautiful, and then we are back to taboo number

one. Besides, if we allow skill back into art, it's Katy bar the

door. If people start looking at paintings again, for any reason,

they won't be paying proper attention to the explanations.

Emotion is not exactly disallowed, but it is discouraged. It

needs to be very muddy and ambiguous. And it needs to be

subordinate to the message. If it is an emotion that can't be put

into words, how is it going to be used to make people think the

right things? The perfect emotion is one that a critic can

explain: one that needs clarification, and a theory to crystalize

it. The worst art is art that is emotional like music. What can

you say about music? The best art is art that is emotional like a

dying woman—a woman being squashed by some big

testosterone-filled thing, like a dumptruck or a stack of porn

magazines. This is what we want.

Subtlety is right out. It is important to differentiate subtlety

and muddiness. Muddiness is good. It requires analysis. Subtlety

is bad. It implies the esoteric. It implies grace and

distinctions. All these terms are signs of the snob. They are

hallmarks of the aristocracy, they betray the odor of the right.

Any hint of the idea of "quality" is as good as an

admission of a belief in hierarchy. As is use of the word

"talent." This word is very incorrect. The "T"

word. It implies distinctions, and distinctions imply inequality.

Depth is taboo for the same

reason. It implies different levels of understanding and thereby

implies the hierarchy. All political intent should be right on

the surface. Muddiness need not imply depth. A bathtub can be

murky. A puddle can have a visually impenetrable layer of scum.

This is what to shoot for. Think Warhol: as depthless as a vinyl

countertop, but theory through and through.

Content. Content was disallowed in the 50's and 60's, but we have

had to let it back in. Pluralism, you know. Appeasement. Work

without content is still preferred, but content that allows for a

left political spin is OK. The only exception is leftist politics

that implies that the future will be all right. Pollyanna art is

boring, and it lures the "left middleclass" into the

bourgeoisie. Learned subject matter is also boring, even if it is

left-leaning. It implies the hierarchy again, it usually suffers

from pretensions of depth and subtlety (there are only

pretensions—"greatness" is a myth), and it often

mirrors "great" art of the past—which is a

categorical mistake. The past is over and there is no going back.

Which brings up. . .

A debt to

the past. This is not allowed. Artists should not admit of the

possibility of any debt to the past. The past is regressive, by

definition. Any similarity or parallel between contemporary work

and work of the past is therefore forbidden. An exception is made

for work that parodies, defames, defaces, belittles, or otherwise

undercuts the work of the past. Artists who take the past

seriously are guilty of a breach of the hierarchy taboo, and open

themselves up to charges of subtlety, depth, beauty and quality.

This brings us to. . .

The

work of the right. Since the right is still stuck in tradition,

their paintings and sculptures, although vastly inferior to art

of the past, nevertheless resemble it in form and content. If a

work by an artist "on the left" were to resemble the

art of the past, it would also, by the commonest syllogism,

resemble art on the right. This is the worst thing imaginable,

and is not to be thought of. Therefore, all progressive art must,

as a first principle, differ in form and content from art of the

past and art on the right. Otherwise it would be too easy for

people to mistake your intentions.

This is just a short list of the most important taboos. There are

of course many, many others. Thou shalt not work small (small

propaganda is no propaganda at all). Thou shalt not write in your

paintings (but if you do, do it either illegibly or in stencil).

Thou shalt not write poetry into your work (but if you do, do it

illegibly, or tongue in cheek, or misquote someone you hate, or

purposely plagiarize). Never rhyme, except as a joke. Never

mention truth, except as a joke. Never do anything well, without

clearly undercutting it. And so on and so on.

In the

current state of affairs—and despite all the claims of absolute

freedom and pluralism and multiculturalism—there is really very

little diversity. There are any number of styles but only two

"schools." And only one of these schools counts.

These two schools are Decoration and Politics. They usually call

themselves "realism" and "the avant garde."

Or Classicism and PoMo. Or whatever. Each has its own market, a

market with very specific boundaries that mirror the boundaries

of current theory in each school. With all the styles you

see—abstraction and realism and impressionism and photorealism

and installation and video and photography and so on—you would

think all the creative possibilities would be covered. You would

think that "there is a place for everyone." You would

think this because you are told this, by the administrators of

art, over and over. But you would be very very wrong.

The first school—Realism, say—likes to think it is a

continuance of tradition. But it is really only a distillation of

it. A thin vapor. Of all the styles and lessons of history, only

a few have remained, in shadowy form. In brushwork, a lot of

Sargent and Monet, a little Rembrandt, a touch of Gauguin now and

then, a tiny bit of Corot or Inness. Either that or hard-edged

photorealism, slick and flat. And almost nothing else. In subject

matter, sailing ships and cowboys and sunsets and flowers and

fruit and barns. Occasionally a portrait; even more rarely, a

"tasteful" nude. And almost nothing else. The lack of

ambition in this school is astonishing. But ambition, in this

market, does not sell. After all, the painting must fit over the

sofa. It must harmonize.

But

that is all beside the point, since according to the experts all

that is not art. It is kitsch. Meaning it is crap. It is painted

by hacks, not artists. It does not count. What does count is

politics. The avant garde is built upon social theory. Art theory

is a subset of social theory. The artist may paint whatever he or

she wants, but it is not relevant unless it can be tied to

current social theory (by writers). Pluralism, that seems so

variable, even chaotic, to the casual observer, is actually all

held together by a single thread. There were two threads at

first, it is true. There used to be "formalism" as well

as politics. Clement Greenberg, the father of American criticism,

had tried to join minimal form to leftist politics; but all the

argument about form died in the sixties, and now only politics is

left. The "form" is now the plural part. It may be

almost anything. But the politics is very specific. Important art

is an art of ideas. Important ideas are ideas about politics.

Important politics are politics that empower the weak (or

confront the strong). This is what art is.

You may say, of course. So what? Art is decoration or politics.

It is pretty things or it is progressive ideas. What else is

there?

There

is all the great art in history.

None of the great art in

history has been defined by either decoration or politics. These

two categories, that exhaust all the current examples, leave out

all the real art in history. Before the 20th century there was a

third category completely removed from decoration and politics.

This category was called art. It is now not only extinct, but its

extinction has gone completely unnoticed.

Take the David

as an example. You will say, it was both decoration and politics.

It decorated the Piazza del Signoria and stood as a symbol of

Florentine power. But I ask you, what is the David

to you? Not to a plaza in Florence or to a 16th century governor.

But to the viewer. I say that to any viewer, 16th century or 21st

century, the David

is a verbally unstatable emotion of beauty and depth. It is a

feeling of awe that vastly transcends any thought of decoration

or any conception of politics. The David is not an idea at all.

It requires no theory. It suffers no context. It does not

harmonize all around it. It is its own thing.

Nor does this just apply to the David.

Some will accuse me of taking an example that has no analogues.

But I claim that all great art is great in the same way, and for

the same reasons—though perhaps rarely on the same level. A

portrait by Titian, a sculpture by Rodin, a landscape by Corot,

an etching by Whistler, a flower by Van Gogh. All these call up

an immediate emotional response that has little to do with

"prettiness" or decoration, and nothing to do with

politics. Visual art is different from the word or the idea in

that it is read directly by the mind, without any verbal

interpretation. In scientific terms, art mostly bypasses the

neocortex and speaks directly to the limbic system. It affects

you like a dream. I say that the more interpretation that is

necessary, the less it is art. If a work makes you think, it has

gone wrong from the beginning.

Please understand that I

am not denying the validity of decoration or politics, or the

importance of the word, or of thinking, or of ideas. And I am

certainly not denying the importance of continuing the fight for

equal-opportunity and fairness. I am pointing out that all

communication does not necessarily concern itself with these

things. I am saying that the political aspect of art is not the

only aspect. It is, in fact, a rather tangential aspect, at best.

But it has turned out to be a predatory aspect. Once it is

admitted to be a part of art, it wants to be all of art. It wants

to redefine art as itself. Art can exist with politics as one of

its influences; but it cannot exist as a subset to politics. Art,

as it is defined now, has engulfed what used to be art, and the

old category is gone.

It is

disallowed. It is not even attempted anymore.

The markets and the buyers would not know what to make of it.

They would not know how to look at it.

Take

as an example the nude above. It is not allowed in the realist

market: it is full-frontal, it has a personal content, it is

direct, it is not especially decorative nor especially beautiful,

it is not very colorful, it is an odd pose and a rather

un-voluptuous girl. The paint is somewhat Sargenty—that is,

bravura and expressive—which would be a good thing if the model

weren't so damned difficult.

It is not allowed by the avant garde for many reasons. First, it

is painted too well. It has a excess of technique. The artist

appears to have studied painting for its own sake, which was

short-sighted of him. He would have been better served to have

read the newspaper. Also, the painting has no definable content.

One has no idea what to think of it. The only politics it seems

to contain is a regressive objectification of the female. The

nude body has not been undercut in any way. The model is entirely

too beautiful (notice the difference here from the realist

market). She is thin and blond—standard jack-off material. Her

gaze is almost edgy enough to allow for a psychological reading.

Unfortunately the artist is a male. If the artist were a female,

we might be able to make something of it. As it is, it is

entirely too sexist—and not in a tongue-in-cheek way.

In much the same way, if not always for the same reasons, the two

markets dismiss almost everything that might have any real

artistic content (by the old definition). What the contemporary

viewer sees as faults, the viewer in the past would have seen as

strengths. What might Whistler have thought of this nude?

For him, I suspect, it would also be a bit too Sargenty (he

didn't care much for Sargent—he thought that Sargent's paint

often outran his painting). But the low tones, the color harmony,

the simple background, the subordination of the composition to

the mood—the means to the end—all these would have appealed

to him. The direct gaze, the strong emotional content, the

non-standard pose—individually expressive—he would also have

liked. He might not have liked the model—she is a little sickly

by Victorian standards—but he most probably would have

understood the connection of her body and pose to the mood

created. At any rate, he would have been struck by the daring of

the piece. It is shockingly intimate, not as in sexy but as in

charged. As in real. She is not sexy like a pin-up or a

porn-star. She looks at you like you are her lover. She knows

you. She is sexy like a whole person, a smart person, a thinking

person. The pubes may be in the center of the painting, but it is

the eyes that swallow you.

If what I say is true, where

does that leave us? Some will say, if art is extinct and no one

has noticed, how is that a problem? Are people likely to demand

the return of something they don't even know was stolen? Do we

really need sonatas and fancy paintings and long boring books? If

people are satisfied with pop culture—by movies and vidgames

and rap and clever installations and limited edition prints—who

are you to browbeat them?

Some

are satisfied and some are not. There remains a large audience

for old books and music and art. These people are not satisfied

by contemporary realism or by the avant garde or by pop culture.

But they do not stand up and demand great works from the present

because they are convinced it is a demand that cannot be met.

They do not want to appear ridiculous. Nor do they wish to seem

unsupportive: it would be uncompassionate to imply that artists

are not already doing their best. So they are silent.

And the artists are silent, too. Historically, artists have

avoided talking about art because we wanted the viewer to know

that art is not about that. Art is not about explanations and

stories and words and ideas. That was one of Whistler's great

notions—to make the analogy between music and painting explicit

by titling his scenes "nocturnes" and "symphonies."

His point was that you don't ask questions about a Beethoven

sonata, why ask questions about a painting? But our silence has

been the door through which the talkers have walked. People

wanted to know things. They wanted to chat. And the critics have

been chatty. They have answered all the questions, even when they

had to talk nonsense to do it. They have filled the magazines and

newspapers and airwaves with their chatter, and they have reaped

the benefits of the social. They have made friends everywhere.

And the taciturn artist has been left on the sofa, nursing his

tonic, while the party moved into the living room. Finally, of

course, the artist was replaced with a cut-out. A bad-boy cut-out

with a cigarette—a two-dimensional prop who was just glad to be

there.

But the party people

are not going to give up the paper hats and the rockin' flat just

because the old artist whispers "fairness" through the

keyhole. No one is going to leave of their own accord. The

drunkards will not listen to reason; they can only be bypassed.

Bypassed by a new dialogue. The silent artists and the silent

connoisseurs must come together and start talking again. They

must remind eachother that they exist. They must remember the

possibilities, the work left to do. The importance of creating

and supporting a living culture. The importance to the future of

believing that history is not over. The feeling of worth this

rightly gives to the present.

If this paper was useful

to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to

the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue

writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused

by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de

plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might

be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33

cents for each transaction.

|