|

return

to homepage

return

to updates

CLIVE

BELL

and

Formalism

by

Miles Mathis

I have

mentioned Clive Bell before in my art papers, namely in a couple

of early papers

that discuss Cezanne. But I have not yet counter-critiqued Bell

with any rigor. Some will ask why I would do so now, given that

Bell is not exactly a household name in art criticism. I do

because I believe that Bell's influence is greater than is

commonly supposed. Much of the burgeoning stature of Cezanne in

the early part of the 20th century was due, one way or the other,

to Bell, and this growing influence of Cezanne and formalism led

directly to where we are now. In other words, the mistakes of

Bell have had a lasting effect on art criticism. These mistakes

are among the foremost mistakes of Modernism, and they have never

been pulled apart to the extent they must be. The mistakes have

acted as a hidden foundation beneath the other more obvious and

more recent mistakes, and it is this foundation that must be

addressed.

Bell was part of the famous Bloomsbury group

that flowered just before the first World War. He was married to

Virginia Woolf's sister, and so was positioned perfectly to write

for the magazines of the time. His first major book and the one I

will counter-critique here, Art,

was published in 1914 but compiled from articles Bell had written

in the years just before that, up to 1913. In this way, Bell

slightly predates his friend Roger Fry, who published Vision

and Design in 1920. Although Fry

published his “Essay in Aesthetics” before Bell really took

off, even Fry admits that Bell got to Cezanne before him, which

may be the deciding factor in all this. Cezanne is their crux, as

Whistler has been mine. In fact, I will argue here along the

lines of Whistler, who would have mocked any painting of Cezanne

and any output of either Fry or Bell as an “Essay on

Inaesthetics.”*

Although the main lines of either Fry's

or Bell's arguments appear at first glance to have a similarity

to Whistler's argument about form, and although the their

arguments have been conflated with his by art critics and artists

who came after, the differences are crucial. Let us see precisely

how. Whistler insisted in his Ten O'Clock Lecture that art was

not about morals or stories or descriptions; rather it was, or

should be, an arrangement of forms. This led, in pretty direct

channels, to Bell insisting that art was defined by “significant

form.” For him, it was not the subject matter that was primary,

or that caused “aesthetic pleasure,” it was the forms. It was

the shapes and colors.

You can see why Bell thought he

was following Whistler, and why many others have thought the

same. If you ignore the context, read in low light, and don't pay

proper attention, you can easily misunderstand Whistler in this

way. Even Swinburne misunderstood Whistler in this way, and it

cost them their friendship. However, I don't blame Whistler for

the misreading of any of these people, Bell, Swinburne, Fry, or

any of the rest. It is their fault for not listening closely

enough. Or perhaps, not being natural painters themselves, they

simply didn't have the ear to hear. Whistler admitted in court,

in his suit against Ruskin, that it “was like pouring notes

into the ears of a deaf man”, trying to make non-artists

understand what art was about. But I will try once more to pour,

and those with ears should try once more to open them.

When

Whistler tried to turn painting away from morals and stories, it

was a reaction to a glut of poor storytelling and hamhanded

moralizing by the painters of the first six decades of the 19th

century. He was therefore forced by circumstance to accentuate

the non-narrative aspects of painting. But we can see just by

looking at his work that he was not interested in jettisoning

subject matter from painting. His works rely on their subject

matter: it is the subjects that have the

forms. Venice was subject matter, and it

had form. His interesting people had form, their dresses had

color, the Thames had fog, and so on. In this way, his painting

was not an arrangement of abstract or theoretical form, it was an

arrangement of real things. It was a selection from life. Nor had

he any idea of jettisoning beauty from painting, since his

arrangements were chosen because they were beautiful. It wouldn't

have been enough for him just to paint a beautiful lady: that

wasn't artistic in itself. No, one must arrange

a beautiful lady in a beautiful composition. It was this

arrangement that was the art of it. That and

actually painting the arrangement. There

was arrangement in the very paint itself, in the way it was

applied.

The lady was already beautiful, and the artist

got no credit for that. It is what the artist did with this lady

that made him a good artist or a poor one. A poor artist could

make even the loveliest lady into a vulgar painting. A good

artist could make a dreary or common scene into a masterpiece.

But this did not make the dreary scene superior to the

lovely lady, as a general subject. Non-artists have misunderstood

such statements by artists to mean that lovely ladies should

never be painted again, or that the only scenes worthy of

painting were dreary or horrid ones. Nothing like that. The only

things artists want to forbid is bad paintings, and you can make

a bad painting of anything. You can ruin a glimpse of heaven, by

improper arrangement.

So, in highlighting the importance

of forms Whistler was in no way discounting subject matter,

beauty, or even storytelling. Whistler wasn't much interested in

storytelling himself, but for him even a narrative or historical

painting could have been successful, as long as it was also

successful as an arrangement of forms. The narrative or history

didn't disqualify a thing from being art, but a story arranged

poorly was like a beautiful woman in a gaudy or gawky

composition: all the art in the thing had been lost, and thereby

the beauty.

Bell never understood this. He took a

highlighting of form as an excuse to jettison non-form, and once

“significant form” became the defining quality of art for

him, all else in a painting could be dismissed. True, Bell didn't

immediately dismiss all other content, but his argument allowed

others to easily push his theory to its inglorious end. To see

what I mean, we only need to study Cezanne. For Bell, the fact

that Cezanne had highlighted the form and played down the rest

was a sort of purification of art. But Whistler would have seen

it differently, I assure you. For although Cezanne was good at

highlighting the form, he was not good at arranging it. His lines

and colors are awkward, unbalanced, and, in a word, vulgar.

Precisely because they lack grace and harmony, Whistler would say

they are inaesthetic. Aesthetics is

this grace and harmony. The forms cannot just be highlighted or

simplified, they have to be arranged aesthetically, which means

they must be arranged and painted

with consummate skill.

Neither Bell nor Fry were very

good painters, which is probably why they thought Cezanne was a

good painter. He was good because he was more like them. Here is

a portrait of Bell by Fry.

You see much of the clumsiness of Cezanne in Fry. Fry was

actually better at figures than Cezanne, but he still wasn't very

good. His line lacked the natural grace of the best painters, and

the same can be said of his color. I think it is entirely

possible that these critics who have championed Cezanne were not

so much championing Cezanne as they were championing themselves.

I suspect that the idea was buried somewhere deep within them

that if they could sell Cezanne to the world, they could

eventually sell themselves to the world. It was a lowering of

standards by roundabout means. And, as it turns out, this is what

eventually happened. The critics began as Fry and Bell did,

subtly turning the field away from grace and harmony by

championing Cezanne and others like him. A few decades later they

would give up this subtlety of argument and admit that they were

undermining art history on purpose. Clement Greenberg was the one

who led this phase of the collapse. And a decade or two later,

these critics had actually taken over art, becoming artists. We

see this first with Barnett Newman, a person with no artistic

ability at all, but great skill at manipulating opinion. After

Newman, this would become the standard. Art had been redefined as

art criticism, and artifacts were no longer created to cause

“aesthetic pleasure.” No, they had fallen far beneath the

original vulgarization of Bell. They were now created to cause a

critical

experience, or to say it another way, a delusion of artistic

relevance. That and to promote the critic as artist.

Yes,

Bell was certainly guilty of a horrible vulgarization of art, but

compared to where art ended up a century later, Bell actually

looks pretty tame now. He knew how to write, had a fairly keen

sense of humor for a critic, a full command of the language, and

said many things that were true. That immediately puts him in an

entirely different category than the current art critic, who

can't put two sensible sentences in a line. Let us look at what

Bell actually said, and see what was true and what was false.

On page 9, Bell says that “we have no way of

recognizing a work of art than our feeling for it.” True,

though Tolstoy said the same thing years earlier. At the bottom

of the same page, he says, “All systems of aesthetics must be

based on personal experience—that is to say, they must be

subjective.” True—and false. All aesthetics must start with

personal experience, as in the feeling one has for particular

works of art. But that does not make aesthetics subjective. Bell

pretends to rigor, but he extends a long misunderstanding of

objective and subjective. Bell implies that all things that are

based on personal experience are subjective, but that isn't so.

According to the original subjective/objective split, a category

could be based on personal experience and still be objective, if

you were experiencing things that were intrinsic to the object.

“Subjective” doesn't mean “based on personal experience.”

It means, “the quality experienced is not in the object, it is

a construct of the mind.” Bell has not proven or argued that

aesthetics is a construct of the mind, or that the object does

not itself have significant form, therefore he has not shown that

art is subjective. He has simply assumed it, on page 9. That is

what one would call a fundamental error of philosophy.

It

doesn't take a lot of esoteric quibbling to show that Bell is

wrong, it only requires showing that objects of art have

significant form in them already, before I experience that form.

In other words, we must ask whether my experience makes the form

significant, or whether it is the form that makes my experience

what it is. Since the form exists before my experience of it and

in the absence of my experience of it, the logical assumption is

that the form causes the experience. If art critics want to argue

the opposite, I would think the burden of proof is on them. How

can my experience of something make that something significant,

if it was not already significant, or potentially significant?

Logically it cannot, so all argument to the contrary is

illogical. I, the viewer, do not make a painting beautiful by

looking at it; it makes me experience beauty. The painting is

primary and the experience is secondary. The painting is cause

and the feeling is effect.

Do I make an apple red by

looking at it? No, something intrinsic to the apple causes my eye

to see red. The eye does not give red to the apple, the apple

gives red to the eye. The eye may translate what it receives,

yes, but it is a receiver. That is the point. The subject

receives and the object gives, not the reverse. We could get that

just from the definitions, without further study; but no matter

how closely we analyze, we come to the same conclusion. Just as

red must be given us by the object, so must any other quantity or

quality, no matter how complex.

Interestingly, Ruskin

understood this perfectly. He had no confusion regarding subject

and object, and no such confusion of aesthetics, so we may assume

that this bastardization of aesthetics was not universal, or not

English at any rate, until the early 20th century. In “Of the

Pathetic Fallacy,”** Ruskin said,

Now,

to get rid of all these ambiguities and troublesome words at

once, be it observed that the word ' Blue' does not mean the

sensation caused by a gentian (flower) on the human eye; but it

means the power of producing that sensation; and this power is

always there, in the thing, whether we are there to experience it

or not, and would remain there though there were not left a man

on the face of the earth. Precisely in the same way gunpowder has

a power of exploding. It will not explode if you put no match to

it. But it has always the power of so exploding, and is therefore

called an explosive compound, which it very positively and

assuredly is, whatever philosophy may say to the contrary.

As

with blue, so with aesthetic form. Paintings are clearly objects

with unchanging forms and colors, and as such they have

unchanging artistic qualities. They are what they are, no matter

what one critic feels or says, or does not feel or does not say,

or what a million such say or feel. Although theories of

aesthetics may be built on personal experiences of viewers,

paintings are not. A theory of painting is not a painting.

Furthermore, theories are neither subjective nor objective.

Experiences are either subjective or objective, but theories are

either true or false. I have shown that the theory that all

experiences are subjective is false, by definition. A dream is a

subjective experience. Looking at a painting is not. And I will

go on to show that many other theories are false. They are false

not because they do not conform to experiences, but because they

do not conform to the information we receive from objects. That

is to say, they do not conform to the facts.

So I have

already shown that the dissolution of art and aesthetics in the

early part of the 20th century was tied to a dissolution in

philosophy. These absurd theories came from critics unable to

make simple logical distinctions, as between a painting and a

theory of painting, or from critics unable to understand

straightforward definitions of words, as in the definitions of

objective and subjective. This is interesting because we find the

same thing in science. On my other website, I have shown a

breakdown in thought in the sciences during the same period. It

would appear that people could no longer think straight about

anything, for reasons yet to be shown. Many have said that the

first World War was the cause, but I think it is clear that the

war was an effect, not a cause. The breakdown of sense occured

before the war, and so could not be caused by it. I will not

pursue the real cause here, but I suggest we would be better

looking for it where Nietzsche looked for it in the 1860's and

70's: in the breakdown of hierarchies and the rise of

“democracy.” I put democracy in quotes there because I have

shown elsewhere that it was not democracy, strictly defined, that

was or is the problem. The problem is a perverted sense of

equality, by which those who have less skill demand equal

consideration. We see that clearly here in this problem, where

people who can't paint well demand equal consideration as artists

or art experts. Real qualifications are ignored, while equality,

equal opinion, and relativism are promoted. This can only promote

a general breakdown of sense, as those with less sense are given

greater and greater pulpits.

We reach another big

philosophical problem with Bell as soon as we reach page 12. Bell

tells us that art is defined by significant form, and that

significant form is form that moves us artistically. That is

circular, and has no real content. It is to define art as that

which has artistic form, which can tell us nothing we didn't

already know. It is like defining redness as that quality which a

red thing has. Of course most definitions are circular like that,

but it does not prevent us from being annoyed with them. A

dictionary is forced to say things like that, the writer of a

book on aesthetics is not. The writer could just as easily write

a book on something else, or keep quiet.

In fact, Bell

begins his book with this pair of sentences:

It

is improbable that more nonsense has been written about

aesthetics than anything else: the literature of the subject is

not large enough for that. It is certain, however, that about no

subject with which I am acquainted has so little been said that

is at all to the purpose.

Unfortunately,

Bell corrects this by simply adding to the literature of the

subject. Defining art as significant form is not to the purpose.

It is more nonsense. It is not false, but it is blather.

Bell

does try to refine this definition a bit, but his refinement is

mainly more blather as well. He says that painting may be

“descriptive”, in which case it has other, lesser, qualities

of art, but is not aesthetic. Aesthetics is not just “suggesting

emotion or conveying information,” it is “being an object of

emotion.” In other words, in descriptive paintings “it is not

their forms but the ideas or information suggested by their forms

that affect us.”

So art must cause emotion directly,

without any mediation by ideas or information. Well, we can see

what Bell intends by this, and he is partially correct. On one

level, this is precisely how art does work. On another level, we

still have a lot of confusion here. Just to start with the most

obvious problem, we have Bell calling art an object of emotion,

when he just told us that art is subjective. If art is an object

of emotion, and is causing us to feel things without any

mediation by ideas, then art can hardly be subjective. Bell has

not only used the word “object” here, he has also used the

word “cause.” The art object is the cause of the aesthetic

response. That is practically the definition of aesthetic

objectivism.

Another problem is Bell's method of

separating the aesthetic from the non-aesthetic, in that he makes

you think the separation can be or should be complete. For the

truth is that aesthetic forms are just non-aesthetic forms

arranged in a certain way, as I pointed out with Whistler.

Whistler is not demanding an arrangement of abstract forms, he is

demanding an arrangement of existing, natural forms. These

existing natural forms are normally descriptive, and they may

still be descriptive after they are arranged, in which case they

will be both descriptive and non-descriptive in the same

painting. So there is no real division into descriptive and

non-descriptive. The categories are not at all exclusive of one

another.

This is crucial, because this misunderstanding

is what led subsequent artists and critics to try to jettison the

descriptive from painting. They thought that by minimizing the

desciptive they could maximize the non-descriptive or aesthetic

part of the painting. See Clement Greenberg, who based his career

on this. But we have seen that this method fails. This

“minimalism” has not maximized aesthetics, it has minimized

it. You cannot make art more artistic by jettisoning all real

objects. As Whistler knew, you make art more artistic by a more

artistic arrangement of real objects.

Why is this so? Why

has it proved impossible to separate the descriptive and the

non-descriptive? Why is abstraction always a ghost, even as

regards emotion? It is because Bell's aesthetic emotion is a

subset of all human emotion, and all human emotion is tied to the

real world. What I mean is that aesthetic emotion is not emotion

in some sort of artistic vacuum, purified from all previous

emotion and knowledge. You feel artistic emotion because you have

felt previous emotion, and all or most of this previous emotion

was felt for real things. That is to say, you cannot feel things

for paintings if you have not felt things for real people or

objects. This is why you cannot separate the descriptive from the

non-descriptive in a work of art. You need both. To elicit an

emotional response, you must have an arrangement of familiar

objects. The unfamiliar can cause no emotion but fear or unease.

The unfamiliar is neither pleasant nor beautiful.

Bell is

correct that it is the arrangement that is the art, although we

knew that from Whistler. But you cannot have an arrangement of

nothing. Nor can you have an arrangement of abstractions. The

arrangement of abstractions can only elicit emotion insofar as it

mimics familiar objects or compositions. An object of aesthetic

emotion is not an abstract form, it is a familiar form arranged

in a pleasing or poignant manner. The human mind is simply not

set up to respond emotionally to the abstract and unfamiliar. It

is set up to respond to the real, which is familiar and thereby

not abstract.

I

will be asked why people respond to abstract paintings, then.

Well, they don't, not strongly. Yes, they may respond to familiar

colors or pleasing patterns, but these responses are generally

quite weak. And in the rare cases that people respond strongly to

abstract paintings, we find it is the idea in the abstraction

that speaks to them, which immediately undercuts Bell's argument.

When I have heard people talk about Rothko, Agnes Martin,

Gottlieb, and so on, I have been struck by the amount of talk

about ideas I hear. For the people who like these paintings, the

abstractions don't seem to be objects of emotion, in the way Bell

is describing. These abstract paintings seem, rather, to be

suggesting ideas

or emotions, which makes them descriptive, by Bell's own

definitions.

As I have said in another paper, an abstract

painting is actually less direct than a descriptive one, since it

has to be interpreted to a greater extent by the mind. The mind

already knows what to make of a descriptive painting, so it is

free to intuit the pleasure in the arrangement. But with an

abstract painting, the mind has to first create a meaning. It

does this, most often, by attaching some previous explanation or

interpretation to the abstraction. It almost needs to have read

about the abstraction before it sees it, to know what to make of

it. It is then unclear if the viewer is feeling something about

the painting or about the explanation of it. Is it the text that

causes the emotion or the painting?

On the other hand, if

it is simply the colors and patterns that are causing pleasure,

it seems to me a weak drink. I have felt a low pleasure from such

paintings, the same sort of pleasure I felt from making God's

eyes with my own chosen yarn in grade school, but I wouldn't

attempt to define all of art on that pleasure. I have felt much

greater things in front of great paintings, and those feelings

can't be explained by Bell's theory of significant form. Form was

only a part of it. Subject matter was always also a large part of

it. It was not one or the other, but a combination.

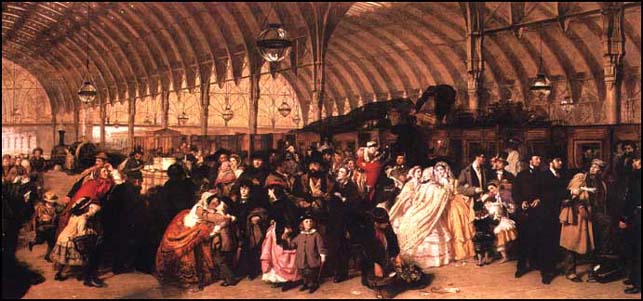

Bell

tells us that Frith's Paddington Station

is not a work of art, but of course that is already going way too

far. It may not be among the greatest works of art, but it is

certainly a work of art. Bell wants to dismiss it simply because

it contains so much description, but that is no reason to dismiss

it. We would be better to critique it on its lack of arrangement,

which is what Whistler would have done. It has plenty of

arrangement, but this arrangement, though done with skill, is not

done with consummate skill. It might have been done better, and

in fact such things have been done better. Bell should have said

that its aesthetic content might have been higher. If he had, I

could not have argued with him.

Bell tells us that in

future we will go to photography to get what Frith is giving us,

and this is one of the places where that idea came from. When we

hear the same sort of thing from Robert Hughes, this is where he

learned it. The falsehood is long-lived. For Bell is wrong once

again. Frith's painting hasn't been replaced in the modern world

by photography, and can't be, since although photography can

catalog events and can even provide some degree of arrangement,

it can't do what Frith has done. Frith has composed this entire

thing, so that Frith's intention and emotion colors the entire

canvas, from corner to corner. No photograph can have that sort

of content. Photographers have a very limited control of their

canvas, compared to painters. Nature herself composes a far

larger percentage of the photo than of the painting, and a large

part of any photo has come to us with no effort or planning by

the photographer. This fact cannot be overlooked. Everything

touched by the human hand has an element of art in it, good or

bad, so that any painting is more artistic than any photo by

definition. Photos are highly interesting and partially

aesthetic, but they can in no way compete with paintings as works

of art. As far as photography has tried to replace what Frith

gave us, we have nothing but a void.

Bell

next dismisses Luke Filde's painting The

Doctor, which is just a smaller painting

of the Frith type. Bell works up quite a hatred of this little

painting, based on nothing as far as I can make out. Bell sees in

it a “sense of complacency in our own pitifulness and

generosity,” but I see nothing of the sort. The painting has a

bit of Hollywood in it, but I don't see the complacency. Who is

being complacent? What is not being done that should be done?

Bell may be implying that they needed better hospitals for the

poor, but this child is not being neglected. A private doctor is

always better than any hospital, as we now know, and this child

is not dying alone in the streets.

Bell says that “art

is above morals,” thinking, perhaps, that this again put him

with Whistler, but it doesn't. Whistler said that art had nothing

really to do with morals, which is true, but that doesn't imply

that the subject of a painting cannot be an explicitly emotional

one. Art can be moral and sentimental at the same time it is

being art. Art doesn't need

to be moral or sentimental, that was Whistler's point. But the

presence of morals or sentiment is not enough to disqualify a

painting from art.

You can see how Bell is an overzealous

hausfrau, sweeping the dinner out with the leavings. In his rush

to define and purify, he has swept the greater part of history's

real artifacts out the door. If we start sweeping out the Friths

and Fildes for being sentimental and descriptive, we have to

sweep out Michelangelo and Raphael, Titian and Botticelli,

Rembrandt and Rodin, Chardin and Corot. Bell usually didn't go

this far, but his theory doesn't give us a place to stop in the

housecleaning. In fact, art criticism quickly went where Bell was

pushing it, and it did dismiss all these artists and most others

as being descriptive, sentimental, moralistic, and so on. All the

art of the past was swept into a pile and dismissed as academic,

Alexandrian, aristocratic, hierarchic, or some other manufactured

and twisted term of abuse.

On page 20, Bell dismisses the

Futurists as inaesthetic, and of course we agree with him there.

The Futurists were strictly political and admitted to caring

nothing for art, so it is not surprising to find politics utterly

swamping art. I would not claim that political content is

disallowed in art, but its presence is always a danger. Politics

always wants to usurp the art, to replace it totally. Politics in

the modern world is much more predatory than morals or sentiment,

since it is much more powerful and ubiquitous. What morals used

to be, politics now is.

Bell then promotes the

primitives, telling us that because primitive art has “no

accurate representation” it is therefore free from descriptive

qualities. That does not follow. Poor description is not thereby

non-description. Beyond that, primitive art is often or always

drenched in religious symbolism. Almost no primitive art was

created strictly as a combination of forms; it was the

representation of an idea. As such, it must have been the

suggestion of

emotion, in the words of Bell. Primitive art was usually in the

form of a totem, and a totem is the exact opposite of a pure

form. Totems are drenched in ideas and rules and morals, so it is

unclear why a Filde painting should get blasted for such content

and primitive art should be sold to us as pure.

Primitive

art proves my point, not Bell's. The simplicity of primitive art

meant that the artifact must be cuing the primitive viewer to

ideas and emotions by its familiarity.

In other words, the primitive viewer already knew what the totem

meant, so its forms didn't need to be precise. It acted only as a

suggestion of what was already known. In this way, primitive art

is actually the least objective and the least aesthetic, by

Bell's own criteria. The idea has already been drummed into the

viewer by previous education, and the art acts only as a

reminder. The arrangement of the forms can therefore be very

clumsy, since the forms only have to roughly match the forms

already in the heads of the viewers. No grace or harmony is

required for this.

We can see that Bell is completely

misdefining what it is that he gets from primitive art. I have no

doubt he is receiving some strong emotion, but I strongly doubt

his report of it. It cannot be his “aesthetic emotion” he is

receiving, so it must be something else. I would suggest he is

being cued to the same cultural memory the original viewer had,

and that it is his distance from this memory that is pleasant. It

is exceedingly pleasant not to be a primitive any more. It is

exceedingly pleasant to dine on ones own elevation. It is

exceedingly pleasant not to live in a tree anymore. Nostalgia may

also be a large part of it. It may be pleasant to remember living

in a tree, provided one does not get cold and wet from the

memory.

But even here, Bell says some very true and

clever things. He says,

Formal

significance loses itself in preoccupation with exact

representation and ostentatious cunning.

True.

Just as politics can and often does usurp art, an overconcern for

precision can as well. Then he says, “A perfectly represented

form can be significant, only it is fatal to sacrifice

significance to representation.” True again. If a simplified

form creates a stronger emotional response, there is no reason to

prefer a more complex form in its stead. However, this must

depend on the situation. Not all emotions or representations call

for the simplest form. Some degree of complexity is often a

requirement of the art at hand.

Bell proves he

misunderstands the limits of his own rules when he says, “But

if a representative form has value, it is as form, not as

representation. . . . The representative element . . . is always

irrelevant.” That is false. If a representative form has value,

it is because the artist understood just how much representation

was required for the art. Since the representation is required

for the art, it cannot be of secondary value or of no value.

Again, it is the combination of representation and of formal

arrangement that is the art. In such a case, right representation

is not a by-product, an add-on, or a accident. It is one of the

fundaments.

On page 26, Bell says, “The significance of

art is unrelated to the significance of life. In this world the

emotions of life find no place. It is a world with emotions of

its own.” No. As I have already said above, this cannot be

true. Bell is blowing at his romantic worst here. I normally come

off as the romantic and idealist against these critics, but I

never say such absurd things as Bell says here. It is simply

precious to claim that art and life can be separated emotionally,

and I have never been a preciosista. Art is special, but it isn't

that special. Art may be a subworld or a superworld, but it isn't

a parallel plane, with its own rules and its own emotions. It is

precisely because Bell can say such things that he can create the

theory he does. Only by believing that art was a world all its

own could you create a theory in which everything to do with life

should be jettisoned. First you state the case and then you try

to make it true. You state that art should be separate, then you

go about separating it. You state that art is not about

representation, then you ditch all representation. You state that

art is not about description, then you ditch all description. You

state that art is not about convention, then you ditch all

convention. You are left with what all otherworlds have always

been left with: nothing.

On page 39, the second page of

chapter 2, Bell begins to wax really loathsome. He says, “Before

the late noon of the Renaissance, art was almost extinct.” He

dismisses Rembrandt to Van Dyck as “tedious portraiture.” I

said above that Bell rarely does what Greenberg does, dismissing

all the greats of Western art, but here we seeing him doing it.

All of art history was only a building up and precursor to his

“Post-Impressionist revival.” While he is showing his

ignorance, he also shows his confusion. He says, “The art of

Poussin, Claude, El Greco, Chardin, Ingres, and Renoir, to name a

few, moves us as that of Giotto and Cezanne.” These are his few

exceptions, we are to understand, but the mix is mysterious. How

do Poussin and Ingres fit into his definitions, especially? With

them we have a hard-edged description, which would appear to

conflict with his previous statements. Are Poussin and Ingres

mainly about forms? If description is superfluous, then a large

part of Ingres must be superfluous. And we find Ingres right next

to Renoir, although Renoir came from the Delacroix side of the

Ingres/Delcroix split. I can make no sense of this list. Bell is

free to prefer them, of course, but he might give us some clue as

to how they fit his theory.

As for the Giotto-Cezanne

pairing, I have never understood it. We continue to get it to

this day, but the joining has never been explained to me. Giotto

is warm and round while Cezanne is cold and square. Giotto is red

while Cezanne is blue. Giotto is almost all figures while Cezanne

is almost no figures. Giotto is big while Cezanne is little.

Giotto is ambitious while Cezanne is not. The only similarity

would appear to be a certain clumsiness in forms, although I

would say Giotto has a naïve charm where Cezanne does not. The

figures of Chardin and Corot bring this naïve charm into later

centuries, but the figures of Cezanne are never charming. Giotto

was the most skilled of his time, whereas Cezanne was among the

least skilled of the famous artists of his time. Like Goya,

Giotto seems to have succeeded brilliantly despite his natural

limitations. Cezanne has not. Even at his best, Cezanne seems

pinched. You can almost read his frustration in the strokes of

paint.

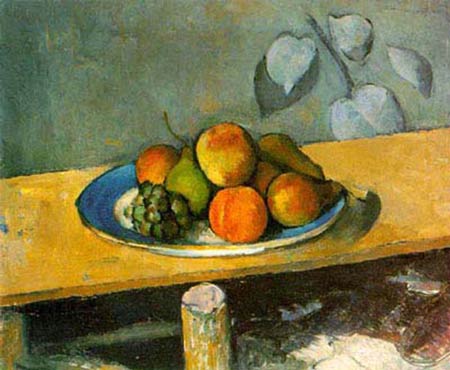

This is not to say there is nothing to like in

Cezanne. As most agree, he was at his best when he limited

himself the most, as with his fruit. But he has been terribly

oversold by the critics, and sold in false terms and similes and

comparisons. He should never be compared to Giotto, and should

never be listed above those “tedious portraitists” like

Rembrandt or Van Dyck. Van Dyck reached pinnacles of grace and

harmony Cezanne never so much as imagined. No one ever arranged

with more skill than Van Dyck. No one. If we judge art simply as

an arrangement of forms and colors, as Bell is trying to do, we

must put Van Dyck at or near the top and Cezanne far below.

Bell says that “Post-Impressionism is accused of being

a negative and destructive creed. In art no creed is healthy that

is anything else.” Absurd and exclamatory, especially

considering that Bell was the most vocal and excitable

cheerleader for Post-Impressionism that any movement ever had or

is ever likely to have. The false praise heaped upon the

Post-Impressionists by Bell and Fry couldn't have been any

louder, longer, more positive, or more overwrought. As just one

example, Bell finishes this chapter by stating,

Tradition

ordered the painter to be photographer, arcobat, archaeologist

and litterateur: Post-Impressionism invites to become an artist.

And just before that he said,

“Post-Impressionism takes its place as part of one of those

huge slopes into which we can divide the history of art and the

spiritual history of mankind.” Good lord, the spiritual history

of mankind, with Cezanne as Christ no doubt. Even Cezanne must

have wondered what he did to deserve this. If he had lived long

enough to witness it, he must have been embarrassed by such

maunderings and noodlings. Bell does everything but get down on

his knees and weep, and we must assume he did that in between

chapters.

On page 50, Bell tempers his loathsomeness

somewhat by speculating that maybe “the artist feels for

material beauty what we feel for a work of art?” Just so,

Clive. You have discovered a nut. But even then, Bell keeps

talking, to his detriment. He speculates that the artist

discovers an object of emotion in material beauty. Yes, but

again, not only that. As above, we have a mixture of the

descriptive and the non-descriptive that is appealing to the

artist. Yes, the forms cause us pleasure, but the forms are never

pure and we don't want them to be pure. It is the mixture that is

most pleasant. We do not desire that life be pure: we are most in

love with the mixture as it is, and do not wish to change it.

That is to say, the material beauty of a woman is for us both

form and description and idea. It is not form separated from

desire or description, but all three. When we paint a woman, say,

we do not wish to sift the form from the rest, because the form

by itself is bare and barren. The form is only pleasant married

to the real. In this way, figuration is like music. To create

harmony, you must have two lines of music playing off one

another. Tempering, likewise. To create a tempered scale, you

must have two notes that dissolve and resolve. It is the

resolution or harmony that is most pleasant, and purification can

only destroy it. Just so with painting.

Bell speculates

further that significant form may be the “thing in itself” or

“ultimate reality”, but again, he is just being hysterical.

There is no thing in itself, if by that one means some deeper

entity hiding behind the descriptive form. As Nietzsche told us,

what we experience is all the reality we can get. Therefore our

experience is real. Our experience already tells us much about

the thing in itself, since our experience is caused by the thing

in itself. Our experience of the thing may not be complete,

because our senses cannot soak up all possible data. But that

does not make our experience false. Nor can Bell's significant

form be taking us beyond the sensible, since how else do we

experience form and color except through our senses? Supposing it

were possible to experience life beyond the senses, we could not

do that through artistic form.

Don't misunderstand me, I

am not saying that there is nothing

behind forms, as Sartre tried to tell us. I am just saying there

is no division. There is not our experience, which is false, and

a reality behind it, which is real. Our experience is real and

something, so there is no nihilism involved. Our experience is

already a direct perception of what is real, therefore we do not

need to postulate something behind this reality. If reality were,

as Sartre said, backed by nothing, we would experience nothing.

Since we experience something, we may already conclude that

reality is something. There is no horrifying void behind

experience, just as there is no deeper reality. Experience is

incomplete, yes, but it is neither shallow nor unreal.

I

am also not saying there is no mystery in art. There is very

much, both in its viewing and its creation. But in art we are not

seeing a deeper reality, since reality is reality. The artistic

arrangement may be heightening and sharpening our senses and our

appreciation, but it is not taking us beyond the senses. A visual

art could hardly do that. An art of significant forms could

hardly be taking us beyond forms.

Bell again tempers his

loathsomeness by speaking, on page 64, “of the absolute

necessity of artistic conventions.” As I said above, Bell

rarely goes as far as Clement Greenberg and his successors. Art

critics after Bell set out to destroy all artistic conventions,

and that told us they were doing it on purpose. But on this

issue, Bell holds back. He understands that art cannot be created

from mist and good intentions. It cannot be created with airy

theories and white canvases, with a bunch of talk and promises.

Bell admits, “The effort would be feeble and the result would

be feeble. That is the danger of aestheticism for the artist.”

Yes, though we could refine that a bit and say “that is the

danger of critical formalism for the artist.” That is the

danger of basing art on critical theories.

On page 67

Bells says,

It is so easy to be

lifelike, that an attempt to be nothing more will never bring

into play the highest emotional and intellectual powers of the

artist. Just as the aesthetic problem is too vague, the

representative problem is too simple.

I

am reminded of a

similar recent claim by the portrait painter Stuart Pearson

Wright, who told us that anyone could create realist images now.

The lie is alive and longstanding, you see. We see that so many

of the current slanders and lies go back before the first World

War, many of them beginning with Bell and Fry. Bell and Fry,

neither of whom could paint beautiful figures, found the

representative problem too easy. “I can't do it, but it is

nonetheless too easy.” And now, because anyone can create

awful, monstrous figures using cameras and projectors and so on,

Wright assures us that realism is easy. But painting figures was

never easy and it isn't easy now. People who do it well are

extremely rare. Good figure painting is so rare now that most

people don't know the difference between bad figuration and good.

No one alive now is as good as Van Dyck. No one alive now is even

as good as Sargent or Bouguereau. So how is it “too easy”?

Bell is partially correct when he says that an attempt to

be nothing more than lifelike is bound to fail, but the best

realists never limited themselves to being lifelike. Good realism

has never been only that. Only a few beginners and hacks limit

themselves to trying to be lifelike, so that Bell's statement is

misdirection. We do not judge art on what a few beginners and

hacks are doing. And besides, Bell has buried his little truth in

a big lie. Telling us that realism is easy is just a hamhanded

attack on skill. It is a poorly disguised bit of resentment. It

is the attempt to replace the skilled by the unskilled, by

telling us that skill is easy or universal and therefore unworthy

of our admiration.

I have only counter-critiqued Bell's

first three chapters, but I think I will save the rest for later.

Sorting through the messes that critics make is sort of like

slogging through a room full of tangled coat hangers, or trying

to unwind a mile long extension cord, tied into knots. It isn't

hard work, that is to say, but it is tiresome. And it is

debilitating to an ordered mind, having to exist among the pages

of a disordered one, even for an hour or two. I begin to get

fluttery and irritable, and I long to hide away in Bach for an

equal amount of time, to reorder the recent chaos. Or to climb

inside a Titian portrait and breathe deep the perfection.

*Whistler mocked Ruskin's Slade

professorship of 1869, and would have mocked even more viciously

the Slade professorship of Fry in 1933.

**This is a must read,

and you can find it here.

If this paper was useful to you

in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the

SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue

writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused

by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de

plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might

be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33

cents for each transaction.

|