return to homepage Relevance as Shibboleth The portraitist Stuart Pearson

Wright gave a lecture [text published in The Jackdaw]

this year at the National Portrait Gallery in London entitled “How Can Portrait

Painting be Made Relevant?”†† My answer

to him is that it can’t be and shouldn’t be, not by his definition of

relevance.† He has asked the wrong

question.† †††††† The publisher of The Jackdaw, David Lee, is always

attacking the avant garde for demanding that art be “challenging”, but from

where I sit the difference between “challenging” and “relevant” is not very

great.† In fact, the avant garde uses

the two words almost interchangeably.†

To be challenging is mainly to be politically relevant, and it is clear

that Wright intends much the same thing.†

He may be a realist and a portraitist, but he has accepted the theory of

the avant garde right down to its roots.†

For him a painting—whether it is a portrait or not—must be judged based

on how well it responds to current culture.†

If it fails to address current attitudes and expectations, it has failed

to be honest.† Any work that is not

honest fails to be good. †††††† I agree with him that honesty is important, but disagree

with all the rest.† Let us begin where

he begins.† Wright opens his argument by

dismissing Annigoni for “refusing to accept that human self-perception had

evolved.”† For him, Annigoni’s treatment

was passe, an attitude from another time.†

From Annigoni’s straightforward portrait of the Queen it is difficult to

tell much about an overall attitude, but taking his oeuvre as a whole, Wright’s

claim is simply false.† Annigoni played

with many little modernisms—in much the same way that Claudio Bravo still

does—putting classical or Biblical themes in modern settings and other “clever”

juxtapositions.† Wright himself is in

this line, although he finds a different set of juxtapositions poignant.† Annigoni and Bravo tweek one set of

conventions and Wright another, but they are not so far apart as Wright appears

to think, especially in their use of realism “to make the viewer think.”† ††††† †For myself, I find

Annigoni and Wright tiresome for precisely the same reason, though I would be

the first to admit that they are very different in some ways.† Since I don’t believe in art “as making the

viewer think”—and since even if I did, I wouldn’t believe that facile

juxtapositions were thought provoking in any important way—I can’t possibly

sign onto Wright’s claim that relevance is the proper adjective to apply to

visual art.† Put simply, when either

Wright or Annigoni is trying hardest to be relevant is when I believe they are

furthest from the true calling of the artist. ††††† Wright’s next two examples are contemporary portrait

painters, and they are both pretty much beside the point, as Wright

admits.† They are bad not because they

are passť but because they are bad.†

They would be bad even if they were au courant.†† In fact, Richard Foster is often quite up

to date in his portrayal of ordinary clients looking pretty ordinary. Red

Sash is not really representative of Foster’s oeuvre, in my opinion.†† Wright blames Foster for poorly updating

Sargent in this painting, meaning he thinks it is a mistake to attempt to

transfer high portraiture into the modern age.†

Conversely, I would say Foster has failed most noticeably in pose,

background, brushwork, color and facial expression.† He has failed to bring Sargent into the modern age simply by

failing to approach him as an artist.†

Sargent tried to make his sitters look very good, and he almost always

succeeded.† Foster is better at making

his sitters look average, which is probably what they were and what they

wanted.† He fails only when he attempts

to make them look really good, since neither they nor him are up to it.† But by Wright’s method of judging, by

honesty alone, Foster could easily claim he is right where he should be—a

journeyman delivering the goods.† †††††† Wright’s other example is George Bruce, and I have little to

add.† He is correct to point out that

Bruce’s settings ring false in every possible way, and Bruce’s technique only

corroborates this falsity.† Even more

obnoxious than Bruce’s chosen settings is his handling of those settings, and

of his sitters.† He could bring the

settings up to date in every way, and yet the paintings would still be

awful.† He would then have badly painted

mannequins trying hard to be relevant but they would still be badly painted

mannequins.† For proof, see Eric Fischl

or Jeff Koons or John Currin, etc.

Wright now jumps from negative

examples to a positive one.† He provides

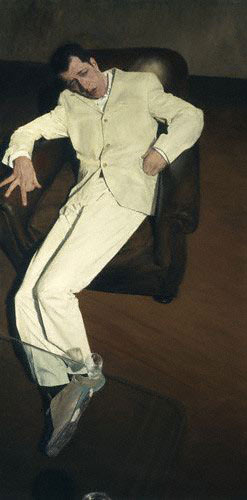

a slide of Phil Hale’s portrait of Thomas Ades, a portrait hanging in the

NPG.† In this portrait both Ades and

Hale are doing everything they can to be odd.†

Hale is looking down on his subject, as if he painted him while hanging

from a light fixture.† Ades is dressed

in a white suit, white shirt, black socks, and comfy shoes.† He is sprawling in a modern comfy chair and

the background is empty.† Ades is doing

very odd things with both hands, one looking more arthritic than artistic and

the other half inside a pocket in an uncomfy way.† His head is cocked hard right and he is looking off camera either

very dejectedly or with great malaise.†

A shot glass appears to balance on one of his shoes, but is actually on a glass table above it.†† †††††† Wright finds this to be one of the best contemporary works

in the collection.† I agree that Hale is

a much better technician than either Foster or Bruce.† In some ways he is better even that Annigoni.† Hale’s technique is completely married to

his expression and his idea and his subject.†

Hale is more innovative, more courageous, and better able to juggle all

the technical issues involved, from composition to color to pose to

brushwork.† If this had been Wright’s

contention, I could not have disagreed.†

But this is not his contention.†

According to the central thesis of the lecture, he considers Hale better

because Hale has accepted that portraiture must be relevant.† Meaning that this portrait is good not

because Hale is a good technician or because his technique is consistent with

his attitude, but because Hale is deconstructing all sorts of things.† All the clever things going on here are

important to Wright.† Ades is not trying

to look good or even presentable, he is trying to be as expressive as

possible.† Expressive has come to be

synonymous with artistic, so how could either sitter or artist go wrong?†† They are accepting their humanity, not

trying to transcend it.† †††††† And yet something has gone terribly wrong here.†† What the viewer is left with is not an idea

of truth or humanity or expression.†

What an honest viewer is left with is this: “a phony painting a

phony.”†† Everybody is trying just too

damn hard.† Despite succeeding on all

the levels I mentioned above, the portrait is still a crashing failure.† It is not appealing to anyone now, except

other phonies, and will not be appealing to anyone in future generations.† Ades comes off as a self-obsessed fake

prodigy in love with his own mannerisms.†

After a few initial question marks, the portrait immediately becomes

tiresome, in the same way that living with self-obsessed fake prodigies

undoubtedly does.† ††††† Now, it might be argued that the world has been taken over by

fakes and phonies, and that an honest art must come to terms with that.† If the world has become a glitzy spectacle

of poseurs and their products, it would be naÔve to ignore it.† Wright might argue that a sane and sober man

who found nothing of interest in gaudy simulacra and who retired in some

seclusion to pursue his non-current pastimes was an anti-intellectual

throwback, one who deserved to be ignored.††

In fact, although he never states it like this, Wright implies exactly

that.† †††††† Annigoni is chastised primarily for existing in a “cultural

vacuum.Ӡ Wright has borrowed that

phrase from the avant garde, and I think the two words together demand a closer

look.† As they are used, they must imply

that current culture is the only road to personal and artistic

fulfillment.† Since everything authentic

exists inside current culture, it must mean that to be outside current culture

is to be in a vacuum.†† But what if

culture itself has become a cultural vacuum?†

What is the honest and authentic response to a cultural vacuum?† What is the genuine artistic response to

culture as a vacuum?† †††† Wright suggests that all artists who do not accept the main

tenets of modernity and of modernity in art must be “unthinking.”†† But what if any deep analysis of those

tenets required that they be rejected?†

Wright never entertains that possibility.† I strongly recommend he look into it.† Even more, I will give him a number of reasons why he should,

taking my examples from art itself, just as he has. I always like to test art

theories by applying them to works that both sides admit are great.† Certain examples always seem to be used by

both sides to bolster argument, and those examples are the ones I like to

return to see how they affect disagreement.†

Let’s go first to Michelangelo’s David.† I notice that the avant garde never uses this sculpture as an

example of art that is passť, dishonest, tacky, inauthentic, or any of the

rest.† Or, to be precise, very few have

made that claim, and none have made it stick.†

Let us ask why that work is great and continues to be great.† Is it because it was relevant, then or now?† No.†

It may have been more relevant then than now, since its initial viewers

were Christian and Florentine, and since it is a sculpture of a Biblical figure

representing the strength of Florence.†

But even then it was not relevant in the sense that Wright means in his

lecture.† It was not au courant

in any way.†† Relevant now means

dismissive of the past and of past ways of thinking.† Wright says so, explicitly.†

But Michelangelo and his Florentine viewers could not agree.† They were accepting stories and morals

created thousands of years earlier.†

Even more, they were accepting ways of representation that were already

thousands of years old.† Michelangelo

was lifting both his subject and his treatment from the distant past and

assuming that it was still relevant to himself and his contemporary

viewer.† And he was right.† It was relevant not in the sense of being

up-to-the-minute; it was relevant in being meaningful.† ††††† What was even more relevant, then as now, was the fact that

the work was beautiful, powerful, deep and subtle, regardless of its theme, its

subject, or its technical pedigree.†† A

proper viewer was and is not much interested in the fact that this is David

from the Old Testament, or that the city-state of Florence is represented and

glorified.†† One must assume that even

the ignorant tradespeople of the time were mostly wowed by the beauty and power

of the work as it is.† They may have

asked who it was supposed to be, just to know, but it is hard to believe that

it ever mattered.† The Italians have

always been honest enough to admit it: they dubbed it Il Gigante, and

the name stuck.†† Obviously, this name

applies to the stone object, not to its subject.† David is not the Giant, he killed the Giant.† But the Italians have always been more than

willing to advertise this confusion to the world.† Psychologically, they could have found no better way to show that

they don’t care who he is.† The only way

they could have been more transparently and gloriously unconcerned with

non-artistic matters is if they had named him that thing in our plaza that

we love. †††††† Now let’s move on to Rembrandt, another artist generally

conceded by all to be great.† Was

Rembrandt relevant to his time or was he not?†

By Wright’s definition, he was not.†

He was relevant only to the extent that he was interesting to enough

people not to starve to death, but he was not relevant enough to have ever been

bought simply because he was up-to-date, or the equivalent of “cool”.† Wright might say that it wasn’t hip to be

hip back then, but Rembrandt wasn’t even stylish by the terms of his own

time.† Like Michelangelo, he looked to

the Bible for themes; and he didn’t find the sexy themes, like Rubens or Van

Dyck did.† He “wasted” a lot of time

with etching, which gave him works that were neither big nor profitable.† He slummed around in the Jewish quarter,

looking for models for his Dinners at Emmaeus and other naÔve and passť

subjects.†† In a nutshell, his PR was

abominable.† He was the sort of person

that a 21st century gallery flees like the plague.† Why is he considered to be great, despite

all this?† Depth, subtlety, power, and

an idiosyncratic technical virtuosity.††

Nothing to do with relevance, not to his own time or ours. †††††† How about Van Dyck?†

Were his portraits relevant, in the way Wright means?† No, not even in his own time.† He was more popular than Rembrandt, and more

stylish.† But he had very little

interest in being relevant.†† Only in

his late portraits did he begin to betray “relevance” and these are the portraits

that have hurt his reputation.† That is

to say, he began to introduce cleverness into his portraits in various ways, to

impress his clients’ mental faculties—to make them think, or to make them think

that he was a thinker.† History has seen

this element in his late portraits as pollution, and rightly so—which turns

Wright’s argument on its head.† Van

Dyck’s greatest mistake was trying to be relevant.†† In his early portraits he is more straightforward.† He puts his sitters in contemporary costume

not to make a statement or to be current, but because that is what they had in

the closet.† Besides, it was more than

serviceable artistically—lots of white ruffle and lots of serious black.†† The same can be said of his best middle or

late portraiture, like the portrait of Frans Snyders in the Frick Collection or

the portrait of Philippe le Roy in the Wallace Collection.† Nothing clever is going on here, no winking

at the audience, no juxtapositions, no contemporary asides, no politics, no

signs or non-signs of modernity.† Just a

sitter in fancy dress, maybe with a handsome dog, with columns or drapery in

the background.† What makes the portrait

great is none of this, though.† What

makes the portrait great is that Van Dyck pulled all these elements, and the technical

elements, together into a perfect harmony of expression and character.† Color harmony, line quality, paint quality:

all exquisite.† Lighting, background,

design: all effortless, all nearly invisible.†

And the overall effect is calm and subtle, high without announcing

elevation.† All art may be manufactured,

in some sense, but the Van Dyck does not feel manufactured like the Hale.† Van Dyck (usually) does not allow his sitter

to overreach himself, to play a game or look absurd.† Van Dyck’s sitters desired gravity and seriousness and beauty,

and they achieved it.† Hale’s sitter appears

to want to be a fascinating character, but does not achieve it. †††††† Now let’s move on to Van Gogh, quite different in some

respects from my other examples.† Very

honest, by all accounts, but relevant?†

Hardly.† He is loved much more

now than he was then, and he is not relevant now at all.† By contemporary standards, his landscapes

and flowers and fruit trees and muddy shoes and girls at the piano must seem

hopelessly naÔve and “unthinking.”†

Someone painting them now would be dismissed out of hand.† And by the standards of his own time, Van

Gogh was backwards in almost every way, in taking religion seriously just as

God was being pronounced dead, in reading books that were considered regressive

even then (like Tolstoy and Michelet and Stowe), in preferring the country to

the city.† What was Van Gogh’s fleeing

Paris for Arles except a flight into seclusion and a dismissal of current

culture?† Of course Vincent gets points

for accepting the cutting edge brushwork and colors of the Impressionists, but one

must ultimately ask if he did this to be modern.† It certainly didn’t do him any good in the markets, and he never

thought to use it to do him any good; therefore it was more of a technical

accident.† Vincent wasn’t the sort to

think of a painting as a novelty, or even as a cultural expression.† And so, to be fair, Wright would have to

deny him credit.† Vincent used some

Impressionist tricks to express his own personal feelings about nature,

feelings which were culturally marginal at best.† He wasn’t responding to the milieu and to the subjects in the

newspapers.†† He was responding to his

own feelings, feelings that were often sentimental, nostalgic, and

romantic.† In fact, this is why he and

Gauguin couldn’t get along.† Gauguin

found him to be an awful rube, hopelessly introverted and out of touch. †††† Which brings us to Gauguin—civilized to his fingertips

compared to Van Gogh—and yet what did Gauguin do but run off to live on a

desert island with naked young girls.†

Did he ever try to be relevant for a moment?† He thought so little of current culture that he erased all signs

of it from his life and art.†

Contemporary critics now use that fact to give him relevance points, as

if he did all that just make a statement, to be “challenging.”† But this is preposterous.† An artist can either flee current culture or

embrace it.† He cannot do both.† If every negative response counts as a

positive, then the argument cannot be falsified and it has no content.† Critics will say that Gauguin found culture

important enough to resist: it proves he was intellectually aware of it.† But this can be said of anyone, Annigoni for

instance.† Annigoni sometimes dismisses

current culture—he is thereby in a vacuum.†

Gauguin dismisses culture and he is fabulously progressive, a man before

his time.† The standards and words are

completely arbitrary, and can be used to include or exclude anyone you

like.† If Gauguin was not in a cultural

vacuum in Tahiti, I don’t know who was. ††††† Of course I do not hold it against him.† I remind you that I think an honest artist

must flee his milieu and this milieu especially.†† All great artists fled or resisted their milieu, and part of

their greatness was their ability to do it successfully.† They existed without that support that is

necessary for most people.† They did not

give a damn what everyone was doing or thinking, whether it was the majority or

the lettered minority.† They did what

was artistically and personally necessary and let the rest go to the

devil.† As† further examples, think of Blake, or Goya, or Caravaggio, or

Rodin, or Munch, or Delacroix, or Courbet.†

Courbet was asked what group he belonged to and he answered, “I am a

Courbetist, that’s all.” ††††† Whistler was another such.†

He could outwrite and outthink any critic of his time or ours, but he

had no time for relevance.† He had his

own agenda and could not be bothered to care what current culture thought of

the matter.† He told current culture what

a booby it was, in no uncertain terms.†

He would also have had an answer for Oscar Wilde, whom Wright quotes

thusly: “Being natural is only a pose, and the most irritating one I

know.Ӡ Whistler would answer that

anyone who considers Wilde an authority on being natural deserves the advice he

receives. ††††† Yet another example is Degas.† Degas is used in current theory as a progressive type, as if his

shopgirls and tarts are meant to be challenging and relevant.†† But in fact Degas was a misanthropic recluse,

an elitist, and a tory.† He thought very

little of democracy and nothing at all of public opinion.†† Current culture was beneath his notice, and

he would not have found it worthwhile to make comment on it for or

against.† His subjects were the surest

form of escape he could think of.†

Gauguin went to Tahiti and Degas hid away in the brothels and backstage

at the ballet, surrounded by a world that was visual only.† How much thinking would you say is required

to paint young women taking off their tutus?††

Once again I remind the reader that I am not criticizing Degas here, I

am extolling him.† He knew how to find

his obsessions, and his politics is beside the point.† Backstage you cannot tell a tory from a communist.† What I want from an artist is great

paintings, not treatises or propaganda or jokes or puzzles. The last part of Wright’s

lecture is given over to Lucian Freud and himself.† Freud is called the Ingres of existentialism “for his sensitivity

to the interior world of the subject.Ӡ

If in fact all of Freud’s subjects’ interior worlds are rotting, flaking,

miscolored corpses, then maybe this is true, but it still begs the question why

Freud meets no one but zombies.† Perhaps

he should try a different neighborhood.††

I must ask, if flattery is dishonest, does that make anti-flattery

honest?† I would think that both are

equally dishonest, since neither one is true.†

Rodin might point to nature when sculpting the Helmet Maker’s

Beautiful Wife: she really did look like that.† But what Freud has done is make beautiful, or at least average

people, look ghastly.† How is this

“getting to the essential qualities that make them human”?† Yes, we will all die, we are all rotting

away slowly inside physically, or at least those of us over 30 are, but is this

our essential quality?† Was the

essential quality of Einstein that he lost his teeth and had bad

digestion?† Was the essential quality of

Marie Curie that she had thinning hair and once suffered from warts?† Was the essential quality of Goethe that his

legs were bitten by bedbugs?† Is the

essential quality of Meryl Streep that she has spider veins and carries

microscopic vermin in her eyelashes? ††††† Freud has deceived us.†

We may not be as princely as Van Dyck made us, but none are as awful as

Freud has made them.†† Kate Moss’ spirit

may be a wretched thing next to her body, but until it is thrown forcibly into

the pit it cannot match the horror of her portrait.† I do not see the honesty or the courage in all this.† We are told that Nietzsche is the father of

existentialism, but he would dismiss Freud as a despiser of life.† Only a despiser of life would call

everything ugly true and everything beautiful false.† He who implies that all beauty is false is a liar.† Freud is either a liar or he must be accused

of selective editing.† He paints only

the ugly.† To retain his honesty, all

his subjects must be ugly inside.†

Knowing the crowd he runs with, this is a distinct possibility, but even

so he still falls to the selective editing critique—a critique invented by the

avant garde.† All the “shallow rejects”

in history have fallen, cut by this sword, from Raphael to Poussin to Canova to

Bouguereau to Sargent, and on and on.††

They have seen and painted only the young and beautiful and perfect, and

perfected that which was not already perfect.†

OK, but, mutatis mutandis, Freud has done the same thing,

painting only the ugly and rotting, and making ugly all that was not already

ugly.† How can lying against beauty be

authentic when lying for beauty is inauthentic?† What we have is a contradiction.†

Nothing as interesting as paradox, mind you, just a contradiction.† A mistake in reasoning. Wright himself is not

interested in ugly for the sake of ugly, at least not in his own painting.† He says he wants “to place the viewer in an

awkward and unfamiliar place between belief and disbelief.† It is my own kind of ‘distancing

effect’”.† Fair enough, but surely this

requires further explanation.† I ask,

“Why?† Distance to cause what?†† What does the journey to the unfamiliar

place achieve?Ӡ Wright appears to have

accepted the “critical distance” of modern art uncritically.† It has been around since the time of Walter

Benjamin and Roger Fry, so it no longer requires explanation.††† We are expected to go, “Ah yes, distance,

always a good thing.† Carry on!”†† But is it a good thing?† I don’t think so.† In my own paintings I don’t want any critical distance, thank

you, and you can keep the critic, too.††

I want the emotional response of my viewer right on top of my painting,

my naked woman sitting on his Id like a cheek pressed on a pillow. †If my viewer has time or inclination to

think, I have done something wrong.††

This is not because I want my image to read like pornography, but

because I want it to read like a purely visual thing, an immediate passionate

response.† All the artists I have

mentioned above wanted precisely the same thing.† Think of Starry Night as the purest example.† The painting grabs you and hugs you so

tightly you haven’t time to take breath, much less think.† Once you break free, you may ask how and why

this is so, but all that is after the fact.†

The artistic response is the first one, and it is the one Vincent was

after.† He could have cared less about

where you went after that.† He was not

in control of where you went after that.†

The artist is responsible for his paintings, not for your book

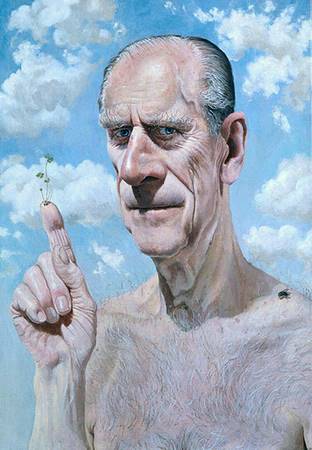

reports.†  ††††††† Wright finds some faults with his portrait of Prince

Philip, but this fault-finding is not terribly convincing.† It is interesting to note that he didn’t

choose to find faults with a painting of a less famous person.† This paragraph can be passed over mainly as

a reminder that he did paint Prince Philip and had four hours with him,

which is four more hours than you had.†

He appears to want to apologize for making Philip look “clownish” or

“like a public idiot” or like a person “not given any accolades for his ideas”,

but I note that he is not above reminding the listener that the Prince is

thought to be all these things.† This

sort of misdirection in speaking is actually an ancient rhetorical device

called litotes, in which the speaker affirms what he seems, on the face

of it, to be denying.† Wright denies

that the Prince is an idiot, but this denial gives him another chance to say,

“that the Prince is an idiot.”†

Rhetorical devices are common among sophists and other people who can’t

just say what they mean directly.† †††††† For myself, Wright’s fake self-criticism further damages a

portrait I was not prone to like in the first place. It seems a cutesy

conglomeration of artsy poses, none of which attach to the Prince

himself—except that he allowed himself to be subjected to it.† I only hope that Wright paid well for the

privilege.† He seems to be paying for it

still.† †††††† Wright claims that the painting veers off course into satire

and caricature, but could it have any other course?† Are we to imagine that a fly on the shoulder and flowers growing

out of the finger were meant for serious commentary?† I am not defending the Prince here.† As an American I know nothing and care nothing about Prince

Philip.† But I do know a dishonest

paragraph when I read it, and an uninspired portrait when I see it.† Wright has already told us that he thinks

portraits must be modern, and nothing is considered more modern than irony and

satire, except maybe double speech posing as depth. ††††††† After all that, only now do I

descend into the whale’s belly.† The

speech as a whole is not just wrongheaded, it is insidious.† It is not just one man’s opinion, take it or

leave it.† It is a sign of a deeper

malaise, both the artist’s and the culture’s.†

And it is a clue to an almost sinister alliance, or capitulation.††† The longer I studied the speech, the

angrier I got.† One reason may be seen

in this line: “Achieving a likeness is, to a degree, a trick with a brush or

pencil, one that can be taught to almost any individual with a modicum of

innate facility.Ӡ Here Wright has

proven himself to be a mole, an enemy in poor disguise, one of Lee’s State Art

people spreading the lie from inside the cathedral.† At a cursory glance, Wright might be seen to be playing the

humble card, but it is a confidence trick.†

Humble or not (I would guess not) he is re-planting the seed.† One of the first seeds and first lies of the

avant garde is that painting realistically is easy, common, and banal.† Once mouthed daily by Greenberg and the rest

back in the 40’s and 50’s, the chorus has returned to full strength.† This lie has once again been given priority

in the war.† Hockney built a new career

upon it and it re-entered the university on his authority.† It has been reconstituted as the Maginot

line against ability.† Because large

numbers of people can create terrible portraits from slides, we are to believe

that the abilities of Van Dyck and Titian have been downgraded.† Because the lowest levels of contemporary

realism are tacky and ill-conceived, we must believe that tackiness is

avoidable, if at all, only by reading the right tracts and thinking the right

avant-garde thoughts.† †††† The fact is, achieving a likeness is damned difficult, and

most people can’t do it even with slides, tracing paper, and every trick known

to man.† Hockney himself proves this in

his own book.† Even among well-paid

portraitists, a good likeness is a rare thing, and an attractive likeness is

almost unknown.† A subtle and graceful likeness

is extinct.† Many painters try to

flatter their clients, but very few can do it.†

You may argue about whether Sargent’s talent for flattery was shallow or

not, but you cannot argue that it wasn’t rare.†

If it had been common then he couldn’t have demanded such huge

prices.† Not one living painter matches

Sargent’s ability, despite a market for it, and despite huge efforts in that

direction.† †††† This makes Wright’s statement misleading at best: it is true

to such a small degree and false to such a large.† The statement has been made by so many people for so long that

most now look at all realism and go, “Pah, anyone can do that.† It is all a trick, like performing magic.”†† And now a realist painter confirms it, in a

lecture at the National Portrait Gallery.††

He has pulled the curtain away and shown us the mirrors.† ††††† But painting is not a trick like sawing a lady in half.†† As a “trick” it is more like dunking a

basketball.† If you can do it, then you

can do it; if you can’t, you can’t.† Some

small percentage of people can add an inch or two to their vertical leap, and

can learn it.† But the vast majority of

people are not tall enough, and that is all there is to it.† Of those that can dunk, only a small

percentage can do it with any style.† They

are very rare, so rare that we can gather them all together for a yearly

contest, and watch them all compete in an hour or two.† This rarity is why they are paid so well. †††† Wright’s statement takes none of this into account, since he

uses the idea just like the avant garde uses it.† He uses the very lowest end of the scale to dismiss the entire

spectrum.† A majority in the arts have

accepted this, but it is an argument without merit or sense.† We can teach eight year olds to dribble and

shoot, but that does not call into question the ability of a Michael

Jordan.† An avant garde logician would

watch Michael Jordan score 60 points and say, “Well, so what, my grandmother

can shoot a basketball.”† Yes, but she misses.† It is hardly equivalent.† By the logic of the avant garde, Michael

should be forced to justify his game with some off-court relevance.†† The NBA should be forced to tart up the

game with gratuitous political references or undercut it with ironic

self-commentary or self-parody.† Wright

implies, by the movement of his speech, that because a couple of mediocre

artists he found on the internet are mediocre, he must eschew straight quality

and begin tarting up his works with some species of cleverness. But the central reason Wright’s

speech is insidious is that he says this: “I feel an increasing ambivalence

toward portrait painting. . . naturalism itself is but a code. . .I am still

indulging in artifice.Ӡ To most this

will seem a pretty tame confession, but to me it is the clincher.† For it leads me to ask why the National

Portrait Gallery could not have hired someone who believed in himself and his

art.† Why was Wright chosen to be the

representative of the opposition?† He

was chosen because he agrees with current theory at almost every point, and

those few points where he strays give him serious pause.† He is a realist and a portrait painter,

which take him about as far from Tracey Emin and the Saatchi people as you are

now allowed to go.† But it turns out

that he hasn’t the balls to actually disagree with them on anything.† He obligingly repeats all their mantras and

apologizes for his own work.† They

hardly need to attack portraiture when he will do it for them.† They hardly need to police his mind when he

has set up the internal guards and cameras already.†† †††††† He sums up with two more central tenets of the avant garde:

“What it means to be human is a perpetually shifting idea,” and, “each period’s

portraits hold a mirror to their time.Ӡ

Both contain a kernel of truth but are predominantly false.† Things do change, hair, clothes, politics,

and so on.† But what it means to be

human does not change, until we stop being human.† That is why, despite losing some of the details, we can follow

the events of history with compassion and understanding.† We can read of ancient Egypt or Rome,

knowing that they were people much like us, who ate, raised families, dreamed,

questioned, and created.†† The portraits

of history do tell us things about the specific time periods, but they were not

created to do so, and their main value then and now was not to mirror

society.† The timeless aspect of all art

is more fundamental to it than its quotidian aspects, and this is true of

portraiture as well.† When I look at

Titian’s Man with a Glove in the Louvre, I am looking at an immediate

communication across five centuries.†

Artistically, the chronological variances are of no import.†† His hairstyle is something I might see on the

street, and his gloves could be bought at the corner store; and even if they

couldn’t, so what?† It is the way Titian

has captured this man that should interest me, that does interest me.† If I am looking at gloves and other details,

then Titian has failed.† The gloves and

such are secondary matters; they exist as part of the harmony and should not

interrupt the main line of music, which is from eye to eye.† †††††† Wright clearly understands none of this.† His lecture serves the entrenched status quo

as another brick in the wall.† It is

another piece of propaganda that the avant garde can use to deflate the

ambitions and passions of young artists.†

If they are attracted to realism, they will fear to "indulge in

artifice."† If they encounter any

genuine emotion, they will feel the need to deflect it or undercut it or

distance it.† If they propose to paint

in any straightforward way, they will chastise themselves as unthinking and

irrelevant.† Wittingly or unwittingly,

Wright has offered up his neck to the chopping block, and with it the heads of

the next generation of artists. If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction. |