|

|

return

to homepage

return

to 2005

The

day after

Groundhog

Day

will

never be the same

by

Miles Mathis

I

was requested to write this article based on recent events at

George Washington University in Washington, D.C. ARC was

informed that the art department there had decided to scrap its

last traditional courses in life drawing and classical painting.

The reason given was that these classes were no longer pertinent

to contemporary artistic expression. The classes were

thought of as a needless limitation upon the creativity of the

students. A well-known and respected teacher there, a fine

artist in his own right who has taught several big names in

current realism, had been told his services were no longer

needed.

Unfortunately,

in pursuing this story, ARC has not been able to obtain the

cooperation of those involved. We are told that the teacher

in question does not want to fight about it. He has

accepted the situation and wants to move on. Another

reporter might leave it at that, but since I am an artist, not a

reporter, I see two stories now where there was one. I see

the story of the latest skirmish in the long-running battle of

real art and phony art and I see the latest example of one side

being too high-minded or too polite or too demoralized to fight.

I will not explicitly assign any of these motives to the teacher

at George Washington University, since I know nothing about

him. But I do know that if I make my claim as a

generalization, I cannot be wrong. The 20th

century has been one long list of examples of real artists who do

not want to fight—“they just want to be left alone to

paint.” Well bully for them. We younger artists

have inherited the world they gave away, and now we have no

choice but to fight. Apparently we must fight them as well,

for they are just as much in our way as anyone else.

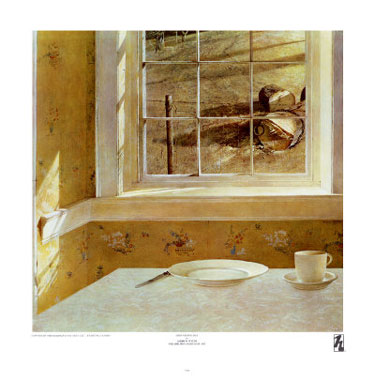

At the

top of this list of people who have not wanted to fight is Andrew

Wyeth, a great great artist who has never uttered a single word

about art in my lifetime. I find this a very

important fact, considering that he has been the most famous

realist in the world for decades. He is the one person who

might have made a difference. He has long had the respect

and the stature to make pronouncements. Many think of him

like a living Rodin or Rubens. But we get nothing—he

doesn’t want to enter the fray. I think of him like J. D.

Salinger, holed up in his New England bower, “I am a rock—I

touch no one and no one touches me.” I will no doubt get

nasty letters from Jamie Wyeth and Bo Bartlett and perhaps a few

others, telling me that Andrew is the nicest man imaginable and

he has the right to do what he wants to do, etc.

Others will say this is not the age of “making

pronouncements.” I answer that a great man does not take

orders from his age. A great artist does not accept the

constrictions of his milieu. If Andrew Wyeth had something

to say, TIME

and Newsweek

and a thousand other places would provide him immediate space.

If he has nothing to say, well, he should

have something to say. If he said what I am saying,

more might be listening.

Any

movement needs both practitioners and leaders. We have had

only the former, and that is why we have not been a movement for

so long. For nearly a century, classical art was no

more than an island thesis, kept alive by Wyeth and a few others.

More recently, classicism has awoken, due mainly to the

leadership of a new handful. Schools have been opened,

societies established. But too few are ready to fight the

real fight against Modernism. They still want to hide away

in their schools and societies, ignoring the bogeyman outside.

We had to open new schools because our fathers and grandfathers

gave away the keys to the public schools. We aren’t even

allowed in there anymore, as the George Washington University

debacle makes clear. They also drove us from the

marketplace, and scant few of us have found our way back in.

All

this we accepted, either as a necessary condition of the new

democracies or socialisms, or as something beyond our control,

like the tides. We talked of being outnumbered, we talked

of this and that, but we did nothing. We took jobs in

advertising, in illustration, in Hollywood, in computer

graphics. If we were lucky. Others took jobs in

coffee shops or delis, painting at night.

But

those who did this had overlooked two very important messages

from history. 1) Numbers have absolutely nothing to do with

leadership. You do not need a majority to start a

revolution. The individual is always mightier than the

group. You just need to stand up and state the truth

clearly; the rest will take care of itself. 2) Modernism is

not based upon any majority. Tom Wolfe pointed this out

most publicly in The Painted

Word. He said that

Modernism was 300 people in New York City and a handful scattered

throughout the world, a few in London, Paris, Brussels, Munich,

Venice and the smaller cities. I suspect he undercounted a

bit, but his point is well-taken nonetheless. If these

people have stolen the history of art, it is because we have

allowed them to. As far as numbers go, the vast majority is

behind us, or would be if we had the courage to stand up.

If we put it to a referendum, we would win by 90%. I have

stated elsewhere that art will not be saved by a plebescite, so I

do not want to contradict myself. I am not suggesting

that we put the history of art up to a vote. But I am

pointing out that our begging off from a statistical argument

doesn’t really wash. If we wanted to use the public as a

pawn—or even as our queen—we could certainly do so.

The reason I have not (yet) attempted to do so is that the queen

tends to march about the board unchallenged, even by her own

subjects. Being jumped over by my own queen would not

be a great deal better than the permanent check-mate I now suffer

under.

What

this all means is that there is and always has been more than

enough grassroots support for real art and ill feeling toward the

avant garde to accomplish anything that needs to be

accomplished. There has simply been no rally. No one

has yet blown the trumpet. No one has marched on city hall,

no one has spent a few nights in jail for the cause. Even

the letter to the editor is rare.

Near

where I live in Belgium is a seaside town called Knokke. It

is a town of art galleries, catering to the wealthy. On the

most prominent spot on the beach they have erected two giant

blobs of white cement, the largest of which looks somewhat like a

nose. It is one of the most embarrassingly ugly and

pointless pieces of public sculpture I have ever seen (and that

is saying a lot). They probably paid a great deal of public

money for it. What is more, the citizens of Knokke know

this. Almost no one likes it. In a democracy or any

other type of egalitarian or socialist society, the will of the

majority is supposed to be sacrosanct. We would be ashamed

to have anything imposed on us in any other way, in any other

arena. But the white blob stands there basically

unopposed. The townspeople are apparently satisfied to have

their artistic ignorance symbolized in that unmistakable way.

Why? Because no one has yet stood up and said, “This

monstrosity must go. It makes us all look bad.”

No one has blown the trumpet, no one has shouted “fear, fire,

foes!” No honest little child has been quoted in the

paper, asking the cutting question, “Mommy, why?”

No one

does this because they are afraid that the media will label them

somehow. They will be a fascist or a throwback or an

elitist. But how hard are these labels to counter, really?

You just don’t stop talking. You say, “No, I’m not,

and I can prove it. And these people beside me are also not

fascists or elitists. They are sensible people who are

tired of having their public places look so ugly and depressing.

They are people from the right, left and center who agree on one

thing, and that thing is that this is not art and that you are

not an artist. Will you please take your blob and go back

to where you came from.” If they wave one flag, you wave

two. If they organize a march, you organize a bigger one.

If they write 10 letters to the paper, you write 20. You

don’t back down.

Knokke’s

problem is the artistic problem of the world. It is the

same problem as George Washington University. A few

people make a decision that affects the whole town, and as long

as the town stays at work or in front of the TV the decision

stands. George Washington University is just the latest

occurrence in a long line of similar decisions. The 20th

century is defined by these decisions, historically.

Private as well as state universities knuckling under to narrow

political concerns; state agencies and national agencies and

foundations falling to the avant garde, disregarding the wishes,

needs and concerns of their own constituencies. The only

thing that is curious about GWU is its timing. It seems a

bit late in the game to be jettisoning craft. One would

have thought that would have been done 50 years ago, at the

least. GWU appears to think that putting up a false

front is no longer cost effective. They don’t seem to see

that Modernism is waning, not waxing. Modern art needs

false fronts now more than ever. It needs to be able to

convince the public that it is “pluralistic.” That

everyone is welcome. It needs the wall of lies because its

façade is crumbling. It has people like me banging away

with heavy hammers at the last bits of mortar, and the only lie

it has left is the lie of invulnerability. But the lie of

invulnerability has never yet persuaded anyone, anywhere, ever.

I

have spent some time in art classes at the university level, and

I can tell you from experience that the wrong classes are being

dismantled. The ones that are useless to a real artist are

the ones that are being kept—the ones where students stand

around in cool clothes, tattoed and pierced, smoking cloves and

buds by the case and talking halfheartedly about the latest

theories. The ones where students punch a hole in a bucket

or glue together a couple of pieces of paper or weld together a

couple of pipes and they have a project. These

students quite literally spend more time thinking about how to

cut their hair and rip their jeans and ducttape their DocMartens

than they do thinking about what to create. This has been

the pattern since the 60’s. There hasn’t been one speck

of progress made since then, despite all the talk of novelty.

The brand of shoes may have changed once or twice in that time,

and the waists of the jeans may get bigger or smaller, but that

is all the news worth reporting. That is the sum total of

creativity from the art departments.

Like

with the citizens of Knokke, you would think that someone

somewhere would be embarrassed by this. But the university

art departments institutionalized this nothingness long ago.

They codified this system, putting it writing, in

unmistakable terms. Their programs and course

descriptions tell prospective students who want to learn

something not to bother applying. Their counselors advise

that any attempt at realism will be looked upon with open

disdain. The teachers themselves often open their sections

with the same warnings. “Do not turn in anything to me

that looks like anything. I will throw it in the trash with

maximum force.” I am not making this up. It has

happened thousands of times; it is happening right now.

Most MFA programs will not enroll realists. If you show a

realist portfolio they will threat you like a beggar refugee or

an alien: someone who just doesn’t get it.

This

is why pluralism is a lie. At the university level, there

is no pluralism, not at GWU or anywhere else. There is only

the avant grade, spray painting trashcans, or collecting urine

samples, or shooting “transgressive” videos. A

realist at the university level would be like Mr. Darcy at an

Eminem concert.

At

other times in art history, this cooption of art by an unpopular

minority would not have been possible. I am thinking

especially of Florence in the 16th century. It

is not true that “everyone was an artist” or a craftsman

then. Florence was a city like any other, where the vast

majority worked in farming or trade. The difference was

that the non-artists still cared about art. The unveiling

of the David was a municipal event, and everyone had an

opinion. They weren’t shy about announcing this opinion

either. You could not have erected a concrete nose and

expected the townspeople to be quiet about it. If you had

shown a transgressive video you would have been stoned or

knifed. They cared, for whatever reason. You could

argue that they didn’t have Tom Cruise or Nicole Kidman to talk

about, so they talked about Michelangelo and Leonardo. But

whatever the reason, things did not pass unnoticed.

Especially things erected in the town square.

Now,

you could erect a functioning black hole on the town square in

any city in America and most people wouldn’t even notice.

An asteroid could fall overnight on the steps of city hall and

most people would walk around it on the way to get their plumbing

license. It’s like a Monty Python skit, except that it

isn’t funny anymore. I remember when I finished my 15

foot Triptych Altarpiece. It wouldn’t fit in my house, so

to test the platform and the backing screws and all that I put it

together in my front yard—a huge naked lady rising from the

water, with poems along both sides, and candles, and the frame

with fish spouting things and waves, and a sculpture in front,

and all lit with spotlights so I could photograph it.

And the neighbors would jog by in their togs, or walk by with

their dogs, and they would glance over and then keep going, no

doubt thinking, “Ah. Another 15 foot triptych

altarpiece. Did I leave the oven on?”

As

a society we take days off for every conceivable event and

non-event. President’s Day, Labor Day, Confederate Hero’s

Day. Why could we not take a day off to actually do

something besides eat fatty foods and drive our cars and throw

litter. We could take one day a month—or even one

day a year—to present a town petition, to solve one

problem, to build one human wall against one specific

encroachment upon our humanity. Must a democracy stop with

voting for someone else to do something for us? Can we not

act ourselves? California has their propositions, but I

have yet to see one that addressed art. Are we really only

concerned about insurance or taxes or organic food? Do our

museums and universities and public places really not concern us?

This

is the trumpet blast! This is call from the

barricades—fear, fire, foes! Your house is

on fire and your children are gone. Or, your museum has

been stolen and your children at the university are smoking

themselves into an early grave. You are spending $20,000

per annum so that they can mark the walls and throw the furniture

out the window.

Ring

the church bell, sound the alarm, man the hoses. The

citizens are with you, they only need rousing from the couch.

You cannot lose. Just don’t stop. Walk by the first

attacks in the paper, walk by the pierced people cursing you with

their little voices, walk by the phony academics, quoting their

specious quotes. None of these is a representative

majority. It is not you that may be ignored.

It is them. Ask for help and you will find it.

All those non-Moderns reading Antonia Byatt or J. R. R. Tolkien

or Umberto Eco (a wide swath that) or watching Pride

and Prejudice or Room

with a View (or even Shakespeare

in Love), those people at the

opera and the ballet, those people shopping for Ophelia

postcards, people studying classical piano or guitar,

bibliophiles, classicists of any kind. Even collectors of

old model trains will understand you. They will be your

natural allies. And if you need a bigger crowd, the average

Joe on the street will join you, with a few words of

explanation. He has no connection to Modernism, would just

as soon see his tax money go to mandatory sex-change operations

as to contemporary museums full of earwax and soggy pillows.

If you can paint a real painting he will choose you every time

over someone who magnifies the trails of dustmites or bottles

flatulence or collects used toothpicks.

And

to those who counsel that the Moderns and Classicists co-exist

peacefully, I ask when have the Moderns ever stopped waging war

for a moment? To counsel peace is to misunderstand the

entire history of Modernism. Modernism is the state

of constant warfare. Modernism is defined as the historical

reaction against art. A Modernist who does not

attack traditions is like a shark that stops swimming. That

is what Modernism is. It is the war and the

warfare and nothing else. Peaceful coexistence between

Modernism and traditional art is like peaceful coexistence

between matter and anti-matter. It is impossible by

definition.

In

this way a request for a ceasefire can only be seen as

disingenuous, at best. “Please stop shooting while we

reload.” Certainly, I would prefer to paint or

pursue other projects, rather than fight. But this is

not the world I live in. I ask my fellow artists, what must

happen before you take offense, before you draw the line and say

no more? You and your children cannot go to public school,

all your institutions have been stolen, your jobs have been

redefined and you have been laid off, you have been slandered and

ostracized, your forefathers and friends have committed suicide,

your cities have been turned into dumps and demolition sets, and

not one sensible word is ever spoken about the thing you love

best.

The

time is now. I name February 3 as the day all the

groundhogs climb from their burrows and see the dark shadow.

Mark your calendar: that is the day you do something. Start

making phonecalls and sending emails now, because that is the day

the world hears the “YOP!” What you do is up to

you. Walk the block, have a committee party, write a letter

and send copies to editors, congressmen, the Freemasons and the

DAR. Put up fliers. Take a megaphone to city hall or

to the museum. Lay down in front of a “work of art.”

Take out an ad. But talk to people, the more people the

better. On this one day, creating a work of art does not

count. You must talk to a real person, even if that real

person is walking by you quickly at the mall because you are

ranting. You must get out of the house.

And

all of those reading this who are not practicing artists, your

voices must be heard too. There are more of you.

Maybe you aren’t as shy as we are. We need your help.

Some of you have asked why art is what it is now. It

is because we have all allowed it to be. If we want real

art and real contemporary museums and real university art

departments, then we must first demand them. We must

believe that art is still possible and still necessary.

There are young Michelangelos and Rembrandts out there right now

waiting to be encouraged, waiting for something to do. For

so long now they have had nothing to do, nowhere to go.

They have been wasted. As a culture it is our job to find

them and set them to work. But we must all get involved.

We must all begin to care again.

Do you

hear that Mr.Wyeth? February

3.

I recommend TIME

magazine or 60

minutes.

If you are camera shy and don’t like to write, dictate a

letter.

If this paper

was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar

(or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me

to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't

be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many

noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee;

so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they

will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.

|