| return to 2005

The Practical Artist

by Miles Mathis

It is possible that some few may get the joke just from reading the title. How could I, of all people, propose to write an article about the “practical artist?” I might as well propose to give stock tips or advice on breast feeding. As it happens, I have no plans to counsel anyone on pragmatism. I am on this page to point out, in characteristically semi-winsome terms, the impossibility of any such beast as a practical artist.

The bookstore shelves are groaning under the weight of artistic how-to books. Anyone who has had the misfortune to wander the aisles of the modern bookstore knows that a proportion nearing one hundred percent of these how-to books concern how to “make it” as an artist. Even the ones that are supposed to be about technique have chapters on making it. And the chapters on technique concern learning a technique that will help you make it. Given this, a contrarian might ask why one never sees a book about not making it. If our culture is so bent on fairness, on multiculturalism, on equal time and so on, why do we not have one single book on how to avoid success in the market? How to be a scrupulous, idealistic, hopelessly romantic artist who thinks the market is a clueless ill-bred whore. That is the title I sought and I got no help from the staff.

I have to wonder that the world does not stutter and stumble to see the words “practical” and “artist” together at all, in any context. Could there be a more transparent oxymoron? What use has society or history for a practical artist? Artists have never been paid for practicality. Do we remember artists for their practicality? Do we read books about the practical artists of the past, to sit in amaze at their feats of bookkeeping? Do we rush to films about Renaissance artists, to see their swashbuckling Technicolor lives of paying bills on time and raising mannered happy children? Would Cellini be more memorable in a buzzcut and bow-tie? Is Leonardo remembered for his bank account? Michelangelo for his summer cottages and IRA’s? Van Gogh for his balanced portfolio of T-bills and mutual funds? Do we care if Picasso was fully insured or if Munch had regular dental check-ups?

Of course, to put it in these terms I have already betrayed myself as an old-fashioned sort of very-strange-person. No one chooses a profession, or acts in any way whatsoever, to be of use to society or history. Practical people do what they do to be of use to themselves, and, if they are exceedingly thoughtful and kind, maybe to their immediate family. What they may sell to others, and how useful it may be in the long run or short, is not the question. The question is what they bring home. Not what is stored away in the annals of time, but what is stored away in the bank. Not what is its value, but what is its price. A thing of no value at all may fetch quite a high price, and often does; while the thing of highest value is given away for free. This situation is of some concern to the idealist, since he recognizes it for what it is. To the pragmatist it means nothing, or it means dinner and new car.

It used to be that a person became an artist because he could not stomach being a businessman. He could not, in good conscience, sell what he was required to sell. But the businessmen finally coopted that field, too, since idealism could be faked as easily as a conscience, and since talent, as a barrier to commerce, could be got rid of too. Some philosophical muddle could be introduced to confuse the issue, and while everybody was scratching their heads, the thief could make off with the pie. It had been done thousands of times in history. No doubt it will be done over and over until the seas swallow up the land.

So now we have the age of the practical artist. The businessman as artist. The walking oxymoron. It starts as a PR contest and ends as a cash contest, Forbes and ARTnews giving us the same sort of ranking based on the same standard. It may make sense, of a sort, to rank bankers or stockbrokers on the pile of coins they sit upon, but artists? You might as well judge chickens by how much milk they produce or fish by how much they can benchpress.

The natural job of the artist is to produce exquisite things. But the gods never guaranteed a market for exquisite things. The recognition of an exquisite thing of course requires an exquisite taste, and the ascendant philosophical muddle teaches that an exquisite taste is something to be rooted out, like a cancer. An exquisite taste, no matter how come by, is like a third ear. Whether you were born with it or acquired it by some strange accident, it can only cause staring and pointing. Best to keep it in a box and don it only at night, undercovers, lest people think you are a reversion or a pestilence.

Imagine some mischievous angel who visits spirits before birth, informing the pre-babes that they will be artists. But they must choose. Since they cannot be both, would they rather be very successful and wealthy, but lacking all talent; or would they rather have an eye for true beauty, and a name that lived through all history, but be unknown in their lifetime? It is clear what choice the practical artist has made. He has traded the reality of being an artist for the name. He has sold his talent and bought a pension, that he and his children might never suffer from want. Not til the years are counted and the money spent will he and his shallow offspring recognize that they wanted all of importance. The idealist artist lived a real life and created real works, while they only spent the inheritance.

Once the choice is well-made and the covenant sealed, all is set for the practical artist. The galleries and buyers are all practical people, so the trio swims along together in a waveless sea, stroke to stroke. The first produces the simulacrum of art, the second sells it and the third buys it, all quite happy with themselves for their cleverness at being part of such a creative scene. None are abashed that the Muse is nowhere represented, that nothing that is exquisite is involved, that art has dissolved and leaked into the air, escaping on an ill-wind. The practical trio has no third ear among them, no least clue of the exquisite. It presence does not thrill them, its absence cannot abash them. The only presence that thrills them is the presence of the Muse Fiscalia. The other Muses arrive at night, slipping silently from the gloom with a subtle kiss. Fiscalia falls from the rafters like a drunken harlot, bejeweled and bedecked in loud colors and noises and tickertape. This is the entertainment they seek, the revelry they pay for and can understand.

And now, in the US, we have that strangest of all beasts in the current menagerie of oxymorons and paradoxes: the Republican artist. The party of practicality is supported by the practical artist. He hires the government to protect his investment from taxation and redistribution. But has no one thought to apply a bit of logic to this absurd situation? Has no one recognized that, even now, we pay the artist to provide passion and emotion and scruple? Though the passion has become bloody and the emotion black, the scruple is still evident even when it is being faked. The excuse for the blood and the black is ultimately the socio-politics it props up. In short, you are being preached at, albeit in very strange words and images. Now, what sensible person hires preachers and prophets and other passionate persons, when these persons are caught in their off hours talking or caring about investments and tax shelters? It would be like hiring engineers who cast runes or like hiring claims adjusters who proceeded by divine inspiration.

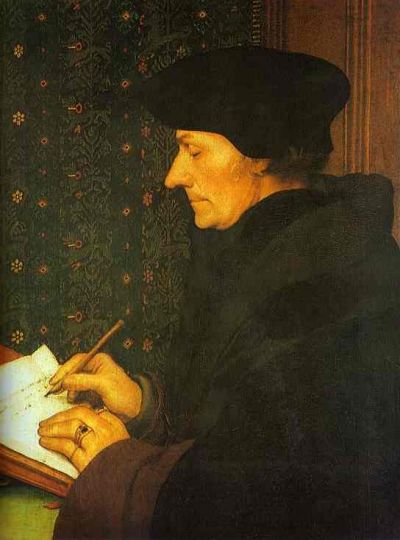

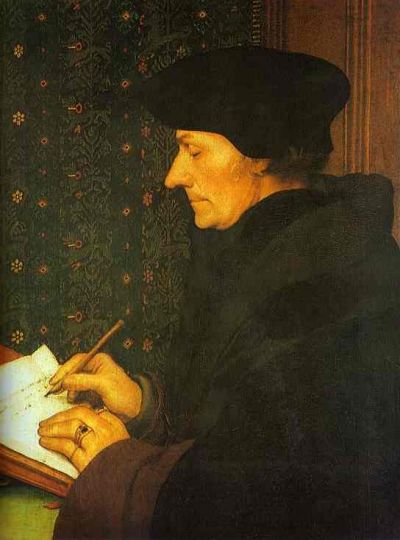

Artists are not practical by nature. What makes them artistic is that they are not practical. That is, they do not judge things by any economic standard. They care nothing for economics, since economics is the most soulless study, and they are interested mainly in soul. They may also have a practical side, as the classical artists had, but they limit this practicality to their study of technique. Beyond technique, they understand that art has nothing to do with practicality. The van Eycks and Durer and Titian and so on were masters of technique, and therefore masters in practice. But in choosing a subject and in expressing that subject, they were not at all practical. The beautiful and the exquisite, the subtle and the mysterious, were their guides.

The exquisite was never achieved by any economic considerations, by any cost-benefit analysis. It is achieved by following another road altogether, a road unmapped by the practical artist. This road leads to a land watered by no streams of gold, no coins are in the fountains there, the kine are not fattened on credit. An artist upon this road, traversing this strange land, has no memory of investments or taxation or any petty fiscal politics whatever. He plucks the fruit from the burthened branches at hand with no thought for the future. He scribbles in the dirt the necessary figures and forms, because they are the ones that must go there. He does not paint into a glittering frame or pre-measure the walls. The frames and walls can be got anyhow.

This all goes to say that if you thoroughly Modern people find your lives lacking romance and passion, perhaps it is because you are paying the wrong suppliers. You have hired the practical artists, the Hollywood pimps and gallery hacks and music-machine mavens who mass produce your paltry passions. Your dreams and desires are prefabricated in photoshop and CGI. You are enriching a class of phonies who do nothing but impoverish you. Real artists cannot be bothered to spend 95% of their time promoting themselves and kissing the asses of galleries and critics. They exist in the unmapped land, where such things do not pertain. They are lying in the lap of the Muse, being sweetly schooled in the exquisite. They cannot waste candle sending you fliers and glowing reviews, studying your throw pillows and your curtains, having their picture taken with celebrities.

If you desire to share in the exquisite, you do not have to follow the real artist all the way into the unmapped land. It can be disorienting in there for someone used to blue skies and sunny verandas. But you do have to get out of the house and poke around a bit. You cannot expect the practical people in your service to arrive with exquisiteness on a tray. They know less than you about exquisiteness or any unmapped lands. You have to go to some real artists’ studios, studios that hedge the unmapped land. Not well-known artists, for the well-known artists are the practical ones, the ones with signs on the door. Do a small bit of work for your exquisite meal. Tramp about a bit in strange streets. Follow hints and clues of other odd persons. And have patience. You will see much that displeases you and some that distresses you. But among this motley band of hooded and cloaked travelers on the forest’s edge, you will find a true companion of the Muse. A thin and ghostly image, perhaps, who may or may not be able to speak well of himself. But he will have your exquisite dream, the thing that delights your eye or ear. That token of a world you thought lost. That spark of your own discarded passion.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.

|