return to homepage

return to 2005

On Talent

by Miles Mathis

In countering David Hockney’s

theory of artistic advance as due to lenses, projection, or photography, two

main types of arguments have predominated.

The first argues that the encouragement of raw talent is the central

cause of artistic advance, in any milieu.

In Greece, in the Renaissance, and in the high cultures of Europe before

1900 highly talented individuals were encouraged and paid well to complete

large and difficult projects. In the middle

ages, they weren’t. Large projects were

mainly group projects (such as the building of churches) and the individual was

expected to be more humble. Modern

artists are also not asked to create ambitious works exhibiting large amounts

of raw talent. They would go against

the beliefs of this age.

The second

explanation offered is that artistic advances have always occurred

simultaneously with advances in other areas, especially science. By this argument, the Renaissance was

caused by a broad cultural flowering.

Discoveries or rediscoveries of things like perspective, field depth,

complex composition, and the perfection of the use of linseed oil as a binder

allowed artists to transcend the woodenness of gothic art. Likewise, the Greek Naissance was caused by

cultural factors. What allowed Greek

art to reach levels never before imagined in history was a broad cultural

flowering. Specifically, the advanced

science of the ancient Greeks rubbed off on the artists, and all the various

boats of art and science were floated on this cultural and scientific

tide. And finally, the 19th

century is offered as the latest example: a time when all things cultural were

being perfected. Science was blooming,

as were medicine, industry, populations, etc.

All contributed to the art produced at the time.

In current scholarship, the first argument is seen as rather

facile and reductive. It seems a gross

oversimplification, for one thing. It

also ignores culture, for the most part, and so it goes against the beliefs of

this age that most things are predominately or completely determined by

culture. For this reason, the second

answer is preferred. Those who can see

through Hockney’s theory are more likely to offer some from of argument two as

proof against it. Argument two is much

richer; it allows for much more to be said with very little effort, since

cultural arguments spring to mind five at a time. And it is less egocentric.

It gives credit not to the individual, but to the broadest possible

group—the culture. Finally, it is

current wisdom as well as traditional wisdom.

The Renaissance has always been explained in these terms, from the time

of Vasari to now. Vasari gave more

credit to the individual artists than current scholars would like to give them;

but, subtracting out his flowery praise to Michelangelo and others, it is easy

to find the beginnings of the cultural explanation in the Renaissance

itself.

Despite all this, I am going to argue that the various

artistic advances cannot be logically explained by argument two. Argument one comes much closer to

explaining them. This is because

argument two only has the appearance of richness. In reality, argument two is the more reductive and

simplistic. It richness is only a surface

richness, a plethora of available examples and subjects for discussion. That is, it is rich only because culture is

complex. There is a lot to talk about. You can spin the argument out in a million

different directions. But obviously

this has nothing to do with the truth of the matter. An argument is not to be preferred for its richness, for the

number of things that can be said. An

argument is to be preferred for its consistency. Argument two is inconsistent.

At first glance, argument two is

very seductive. It seems to make sense

because all its assumptions are both true and commonsensical. It is true that artistic advances have often

gone hand in hand with scientific and cultural advances. It is true that there

has been cross-pollination between the various sciences and arts and that

culture certainly affects all things in that culture. It is therefore easy to jump to the conclusion that culture caused

artistic advances. That is to say,

artists in the Renaissance were better because they benefited from a superior

culture, one that taught them perspective, supplied them with good materials,

and so on.

However on closer inspection this conclusion begins to

break down. The conclusion goes far

beyond the assumptions. First of all artistic

advances haven’t always gone hand in hand with scientific and cultural

advances, and the 20th century is the best example. No matter what you think of modern

governments or economic systems, it is undeniable that the 20th

century was the most advanced technologically and medically. It was also the most advanced in terms of

equal opportunity, giving unheard of freedoms to women, children, minorities,

workers, the poor, and many others.

And yet art has deconstructed or self-destructed.

This is not the most telling counterexample, though. A greater problem is encountered when you

look at the time period between the Greek Naissance and the Italian

Renaissance, and attempt to explain the reversion to a naïve technique. We are fairly certain that the Greeks could

paint as well as they sculpted, although no masterpieces by artists such as

Apelles survive. Whether he painted

like Titian or the slightly more naïve Botticelli is not really to the point

here. My belief is that although he could

have painted like Titian if he had wanted or needed to, he purposely chose to

paint in a more stylized manner, even when doing portraits. Reasons behind this belief will be shared

later; for now it is enough to assume that the Greeks had reached a level of

art on a par with the High Renaissance in most ways. If this is true, it becomes difficult to explain the loss of

this ability in the middle ages.

Customs change, but abilities are not lost so easily. I have two reasons for saying so. One is that it is counterintuitive to assume

that a talent for drawing or painting can be part of the human package in one

age, and gone a few hundred years later.

Can the Gothic painters and sculptors really have just forgotten how to

look at the world closely? Could they

have lost the basic ability to notice that things that are farther away look

smaller? Could they have forgotten how

to put things in complex arrangements?

If so, we might imagine that their flower arrangements also became

simple and vertical, that their language became terse and stilted, and that

their dances became short and robotic.

And we must imagine that all these things became true because they were

no longer capable of anything else.

They quite suddenly became stupid; and then, just as suddenly, became

smart again, only because someone rediscovered perspective, dug up some old

statues, and began to read some old books.

The second reason I doubt that abilities can be lost so

easily is that my own experience contradicts it. In using this as a reason I must make a small digression, for you

will ask, “How can personal experience be a counterexample to a movement of

history, or a theory of history?” Quite

easily, actually. Personal experience

is generally not accepted as a serious argument due to the fact that it seems

so feeble next to the experience of culture.

Scientific and cultural knowledge is a compilation and distillation of

the experiences and discoveries of thousands or millions of individuals. It must therefore trump all personal

experience. But this could be true only

if a culture were judging the argument.

In fact, a culture can do no such thing. A culture cannot read one book, make one distinction, or come to

a single conclusion. Only individuals

can do that. And if you look at any

theory of knowledge from the perspective of an individual, you see that

personal experience is actually the most certain knowledge of all. Not for the reasons Descartes gave, or for

any idealistic reasons either (as in the Idealism of Berkeley). Personal experience is the most certain

since it is the only set of facts that any of us has that is verifiable both

internally and externally.

What I mean by that is that each of us gets our information

from three possible sources: 1) Dead people, 2) Living people, 3) Our own

experience. From dead people we get

history, which is always liable to have been polluted by other dead people as

well as by living people. We don’t know

whether to trust old books, and we don’t know whether to trust living

people. So history is potentially

doubly compromised. Dead people can be

lying in the books, and living people can be lying about the books. Likewise, information from living people is

also doubly compromised. Living people,

even if they aren’t outright liars, can be hedging, they can have an agenda,

they can be spinning. And even if they

are completely scrupulous and transparent, they can be badly educated by dead

people (books) and living people (teachers) so that all their information is

useless.

Modern psychologists tell us that our own brains are just as

likely to lie to us as other people are, and logic implies that we ourselves

may be just as poorly educated as anyone else.

And yet I would argue that there is still a degree of transparency in

analyzing ones own thoughts that is unavailable anywhere else. I have never accepted the behaviorists’

claim that subjective experience is the most useless thing of all to science. Other people’s subjective experience

may be useless to me as a scientist, since that experience is not verifiable by

me beyond what they say or do. But my

own experience is verifiable, since I can easily prove a correspondence between

what I say and what is in my head. I

have direct access to both places.

You will say that this direct access is useless to you as

the reader. It is unless it happens to

be the same experience that you have, and you can verify it by looking within

your own mind. In which case it becomes

more certain than anything else can be.

You will have verified my statement by your own internal system, in

which case it will become to you as your own truth. My verification becomes your own verification. This is how real agreement and understanding

is reached in the real world. And it is

why shared experience works as a justifiable standard of truth. [Not fully justified—as in absolutely

certain—but justified as in having good reasons, or as in being preferred to

that which is demonstrably less justified (such as taking someone else’s

word for it)].

Now back to the central thesis of the paper. My personal experience as an artist

contradicts the historical explanation of artistic advances in the Renaissance

and of regression in the middle ages.

It does so because I know that the state of culture had absolutely

nothing to do with my own innate abilities or my progress as an artist. My ontogeny does not recapitulate the

phylogeny. My personal progression does

not verify art history. It flatly

contradicts it. If culture causes, or

even influences, artistic ability, then one would expect that artists in any

age would have to learn art from their culture. If Renaissance artists knew perspective and Gothic artists did

not, then it is because the Renaissance artists were taught perspective. If they had not been taught perspective,

they would have been ignorant of it, like their grandfathers. On the other hand, if knowledge of

perspective is innate, even in some artists, then culture cannot be assumed to

be the cause of artistic advance.

I myself had an innate knowledge of perspective, and I have

proof of this not only in my own mind—as in having a memory of knowing what I

know and having never been taught it—but also in the form of early drawings

that show it incontestably. In my

babybook there is a train that I drew when I was three where the back of the

train gets progressively smaller. It is

dated and my mother has written below it what I said at the time. She asked me why the caboose was

smaller. I said, because it is farther

away. My parents were not artists; we

had no art books in the house. My

parents never talked of perspective and certainly never showed me how to look

at a train, much less a painting. I

have never seen a drawing that either of my parents ever made. I am not sure they can draw anything with

perspective even now, not even a table or a box.

I was drawing portraits by the time I was four. By the time I was six they were

differentiated and recognizable as individuals. By the time I was eight they were precise renderings, simple but

accurate. When asked to explain my abilities, I was straightforward: I simply copied what I saw. There was nothing mysterious about it. In my own mind it was exactly the same skill

as forging a signature, another thing I was proficient at by age 10. I saw a complex line and I copied it,

disregarding whether that line outlined a head or looped into a signature. In second grade I was already known for

being able to reproduce any of several comic strips. Not trace or copy, but memorize and produce on demand, to the

delight of my classmates.

Before I could walk I was copying figures. My mother was working on her PhD in

mathematics during my earliest years, and she would sit at a card table doing

her equations. I would sit under the

table in my diapers and try to stay out of trouble, I suppose. One time she got up to answer the phone or

the door and a pencil and paper fell to the floor. By the time she got back, I had copied her equations in a

wavering baby line. She was horrified

to think that I was some sort of mathematical freak [Discovering that I was an artistic freak was comforting for some

reason—I can only suppose because it could more easily be ignored. A mathematical freak was just far enough

from normalcy to be scary. An artistic

freak was so far outside the experience of my parents that it did not even

register.]

At age 11, I took a two-week summer class at the Garden &

Art Center. This was my first art

class. Even before the class I was

already producing fully shaded drawings, mostly of animals. I made these drawings freehand, either by

copying other drawings or by copying magazine photos. I did not trace, nor did I use sight-size, calipers, rulers, or

any other devices. I could already

blow images up or down at will. I

was able to do this the first time I tried. Of course I could also draw from life, provided my subject sat

still (I did not produce any cougars or deer from life for obvious

reasons).

I learned

nothing of use in the class, my only benefit being the bit of prestige I gained

by being further singled out. My

teacher at the Art Center was mystified by my ability, and she asked me

(privately) if I drew from light to dark or dark to light. I had to think about it. I still have to think about the answer,

since I don’t really do either and never did.

I never had a conscious method.

I certainly didn’t draw from light to dark, since by my way of thinking

in a pencil drawing you only draw the darks.

The lights are what are left over.

But you don’t draw from dark to light either, since you start with the

outline—which is never the darkest dark.

In a nutshell you draw the most important things first, and these

include the outline, the placement of the eyes and mouth and other reference

points (like the belly button or areoles in a nude, or the points of

intersection in a complex design).

Now my answer would be that you start with the midtones and work out

toward both darks and light simultaneously.

But I did not discover this until I began using pastels, where you had a

range of lights as well as a range of darks.

Some may argue that my use of the word “innate” is

imprecise here. It would be just as

easy to claim that I taught myself perspective by noticing, on my own and very

early, very subtle differences in my environment. In this case, the knowledge was not innate, since I was not born

with it. In fact, I agree with this

distinction. I do think that all babies

learn by automatically abstracting out certain features from the totality of

experience. The idea of distance is one

such abstract feature. Some artistic

toddlers go a bit further and notice what we call perspective, a subtler

refinement of distance. However, in

either case my contention is supported by the facts, since whether perspective

is innate or intuited in the first years makes no difference. Culture is not responsible for either innate

ideas or intuited ideas. And, beyond

this, it is obviously quite easy to say that the ability to resolve complex

ideas from experience is innate, or that the ability to intuit (to learn

without being taught) is innate.

All this goes to show that artistic ability may be, and in my

opinion usually is, no function of the culture at all. Critics might retort that my experience

would only be possible in a culture saturated with images. But this doesn’t explain my experience, not

by a long shot. No doubt I was

influenced by printed images from an early age, from Dr. Seuss and Charles

Schultz in my early years to magazine photos in my teens (TV was always beside

the point, since you couldn’t draw from TV images—they were strictly equivalent

to real life moving “images.” It is

impossible to claim that ancient artists would have benefited from TV, since no

artists have ever been short of moving images.) But these images were in no way the cause of my

progression. For one thing, none of my

experiences up to age three could explain my understanding of perspective. Images in toddler books are not much help in

teaching perspective. And besides, the

cultural argument requires that one be explicitly taught perspective, since it

is not something that a person would notice without being taught. Otherwise the Gothic artists would have

picked it up from their toddling experiences.

Beyond that, I was drawing portraits from life before I was

copying images from magazines. I did

not learn to look at people like photographs.

I knew how to look at both people and photographs (and signatures and

comics) more closely than other people did.

It was innate. It was what used

to be called a talent.

One of my best friends has related his experiences, and

they are the same. He never learned any

techniques, never took any art classes, never went to college, never learned

about perspective, sight-size, or anatomy.

Never did dissections, never studied optics. Never read criticism.

Knew nothing about art history.

And yet he could always draw or sculpt anything he wanted to, as far back

as he can remember. He knows some art

history now, and has caught up in many subjects, but all these readings were

after the fact. They could not have caused

his ability, since they postdated it.

He is as lousy at explaining his method as I am, since in his mind he

just copies what he sees. He explains

color mixing this way: “If I want it bluer I add blue, if I want it redder, I

add red.” Hard to argue with that.

It is not a popular method or ingratiating technique to mention

talent, especially ones own. But

someone must broach the subject, and it is best to do so with full

honesty. I believe that my argument

will be convincing to many other artists, since it will correlate with their

own experiences. Drawing and perspective and color mixing and the recognition

of color harmony and composition are all innate abilities. They can all be improved with practice, but

they are there from the beginning, already in advanced form in some

individuals. These individuals do not have

to be taught. Many will admit this, but

few have seen that this is a nail in the coffin of the cultural explanation of

artistic advances in history, and of stylistic differences between ages. In the middle ages, artists didn’t forget

how to look at the world or how to draw.

They just weren’t encouraged to draw, and in the rare cases they were

encouraged to draw, they were encouraged to draw in the way they drew. If a child drew a realistic figure he was

punished, or it was thrown away or lost.

If the child drew an iconic looking figure, he was sent to the monastery

to paint icons. It is obvious what sort

of figures a child would draw under such circumstances, a child who does not

want to spend his life hoeing corn.

By this reasoning, culture cannot cause ambitious

or complex art, it can only prevent it.

Culture has much more power as a negative factor than as a positive

factor. This is not to say that

culture has zero influence as a positive factor. Lorenzo de Medici was certainly a positive factor in the life of

Michelangelo, as were the various Popes.

But they and other people of the age made the various artistic works of

the age possible only by making a place for them, not by some sort of cultural

construction. Michelangelo didn’t have

to go through a long period of schooling where he learned perspective, anatomy,

optics, criticism, composition, and so on.

He was creating advanced works in his teens, before he had read any of

the great books of his time or the various treatises on art or culture or

technique. His culture did not create

him, it simply got out of his way. The

Church had been holding artists back for centuries and in the Renaissance it

simply stopped doing so, in many ways.

Society no longer wanted small flat icons or humble decorations. It wanted grand decorations and large

complex sculptures. The artists were

almost immediately able to produce these works. If it took a few years to perfect the system, it was not to give

artists time to stoke up their genes or to read texts or to go to school, it

was to broaden the studio system enough so that the few with the most talent

were found and added to it.

No doubt there were youngsters in the middle ages with the

innate talents of Raphael or Titian.

There was just no call for such paintings. The talent therefore remained dormant. As soon as there was a call for the talent, it was expressed, for

this is exactly what the Renaissance was, in the first instance. It was not a cultural flowering, it was a call

to talent to awaken. The awakened

talent caused the flowering, not vice versa.

Culture did not create talent, talent created culture. Culture’s only use was to encourage talent;

not, as I have already said, by teaching it or creating it, but only by finding

it and giving it things to do. There is

certainly a give and take here, a sort of hermeneutic spiral, but talent is its

driving force, not culture. Culture

cannot create talent, but talent can create culture. Culture is simply the summation of the outputs of talent.

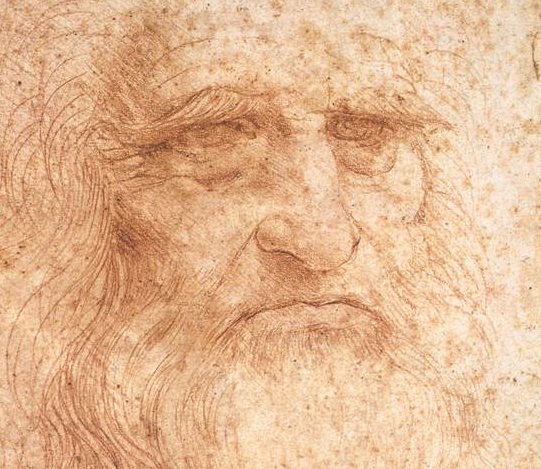

A skeptic will ask me how to explain the gradual advance from Gothic art to Giotto to Massacio to Verrocchio to Leonardo. According to my theory, why did Giotto not paint like Leonardo or Holbein to start with? If the talent was already there, in latent form, why did it not flower immediately? There are many reasons, but the most basic one is that Giotto was not Leonardo. He was Giotto, working with his own limitations. Barriers are broken down by degrees, and opportunities do not reach everyone in a culture at the same time. It wasn’t that Italy created artistic equal opportunity overnight, by edict or proclamation, sending out invitations to every household in the land to apply for positions. There wasn’t a national search for talent, like dance masters from the Kirov spanning Russia to find the next prima ballerina. At the time of Giotto, the barriers were just beginning to crumble, and Giotto was an insider who benefited. The limitations of his art are therefore a combination of his own limitations and the limitations of the system he was a part of. His successes accelerated the process, so that more interest was generated in art, and more freedom granted to it. More young people considered art as a possible vocation, and more families looked at it that way also. The guilds expanded and so did the markets. This was an invitation to talent. This process played itself out over the next century, until a few of the most talented (mostly male) youths in Italy were drawn into the field. Even then, we have no way of knowing that Leonardo and Michelangelo were the most talented people in Italy. It is possible that even greater talents were wasted in the fields or in the wars or wasted by being not being male.

Leonardo did not stand on the shoulders of giants in the way

that is commonly meant. He did not

somehow internalize the knowledge they had gained over the past century. He did not study Giotto and the others,

zipping through a hundred years of education and progression in just a few

months of study. They made him possible

not by education or example; they made him possible mainly by perfecting a

system in which he could be free to do as he pleased. Verrocchio did little for Leonardo except provide a studio in

which he could be discovered. He

provided him with nothing but a precedent he could immediately surpass.

Why was Leonardo better than Verrocchio? He was better

because he had more talent. He was

always going to be better than Giotto or Masaccio or Verrocchio, no matter the

cultural context, as long as the context was enabling in any way. Leonardo’s culture was no more a cause of

his talent than it was a cause of Verrocchio’s. Italy was encouraging to them both. Verrocchio was just lucky that the system hadn’t been in place

long enough in his youth to have yet found many Leonardos.

Another example is the

technical advance that took place in the Renaissance. Current and traditional wisdom has told us that the perfection of

various oils as binders (and other technical inventions) was partial cause of

the Renaissance, and this is chalked up as another gift of culture. However, it was not culture that discovered

and perfected the use of oils as binders, it was individual artists. The van Eycks made perhaps the greatest

contribution in the use of binding oils.

This implies that great artists will make great art with or without

previously established methods. They

will do what needs to be done in each circumstance, and if a technique is not

already available, they will immediately invent one. Many other artists in the Renaissance had personal recipes that

varied to a very great extent, concerning binders, mediums, grounds, and

supports, as well as the making of brushes.

Some of these have turned out to be less permanent than others, but this

is beyond the question at hand.

The same could be said of Greek painters, who may or may

not have had techniques as useful as those of the Renaissance and

post-Renaissance. We know they were not

permanent, but they may have been as permanent as the most permanent techniques

in history. For example, Titian’s

technique is the most permanent known to us, but it has been tested for only

500 years. Apelles’ paintings may have

lasted 500 years, but they would still have crumbled some time in the first or

second century. All of this is beside

the point, though, since what is being debated is whether the techniques worked

at the time. They obviously did so,

since we still hear of Apelles’ fame.

Likewise with Leonardo. The

Last Supper was a great success (even technically) for a few years at

least, otherwise it would not have been as famous as it was. The technique used was invented for the

specific occasion by Leonardo, therefore it was not a gift of culture. It was a free invention by an

individual.

Fresco painting was also invented by an individual, as was

everything that we know of. Culture can

invent nothing, since culture is an abstraction. Everything in culture came from the mind of some person. Culture is not creative; culture is not even

active. Culture can do nothing. Culture is the name given to a summation of

actions or inventions or ideas that all came from real people. Not people acting as groups, but people

acting as individuals.

A critic will answer, what about votes?—votes are group

actions that have cultural implications.

They are creative and they are active.

Yes, but they are also direct summations and so further prove my

point. Group votes are ultimately

explainable as individual choices. Just

look at the way we get a group vote: we add the votes together. That is the definition of a summation. The total vote count has no content that is

not in the content of each individual vote.

The whole is not greater than the parts. The whole is the parts.

But nature and history are not

democratic. Very little that has been

done in history, and nothing that has been done by nature, are democratic. Art history has never proceeded by vote or

general will. Art history, indeed all

of history, is hierarchical. The

progression of art history has been decided by a few thousand artists among

billions of people in world history.

The movement of art history in the Renaissance was determined only in

small part by culture as a whole, by the input of writers, connoisseurs, Popes,

and princes. It was not determined at

all by the masses. The extent that

non-artists affected art in the Renaissance was limited to their roles as

providers of projects and of encouragement.

By far the greatest determination of the progression of art in the

Renaissance was provided by a handful of artists—Leonardo, Michelangelo,

Raphael, and others. Fueled mostly by

innate abilities and instincts, they led the way and the centuries have

followed. When the centuries have not

followed, it has been due to the innate abilities and instincts of other great

artists, artists who freely invented or synthesized new forms, techniques, compositions,

or subjects.

In my mind, this has always

been self-evident. It is proved by my

own experience, by my readings of history, and by every analyzed idea I have

ever encountered. It has taken me many

years to realize that this is not current or traditional wisdom, that it is not

accepted by the majority of writers or critics, and that it is no longer even

the go-to opinion of the uneducated or naïve.

It is not a majority opinion for a simple reason: it is an opinion that does not benefit the

prejudices of the majority. It is an

undemocratic and unegalitarian opinion.

Its content is that people are not equal and that they do not contribute

equally to specific arenas, like art or science or even history. Not only am I saying that not everyone is

an artist, I am saying that culture as a whole has very little say about

art. Not only are the masses left out

of the equation, but even princes and Popes and writers and critics are left

out of it. The cultural influence on

art, from almost every quarter, is usually negative, the only possible positive

influence being the creation of projects and encouragement.

Of course this says nothing about equal opportunity or

democracy as a principle in government, or about fairness, or about universal

rights. It can very easily be argued

that although nature is not fair in her disbursement of abilities, people

should be fair in their treatment of one another. I am very far from arguing for any type of social Darwinism or

fascism. Although I believe that

hierarchies must and should survive in governance, I do not believe these

hierarchies should be based on class or wealth or sex or race or age. They should be based on the ability to

govern, that is, on the ability to comprehend complex situations, make

impartial judgments, and lead by example.

And equal opportunity is just as logical a first principle in

hierarchies as it is in communes, since it is the primary guarantee that talent

and ability will be found, whether that talent is for governance or for

creating great art.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.