| return to 2005 Nietzsche v. the Amish Since I have agreed with Tolstoy that expression is the

central concept in the definition of art, I feel that I now must explain how

beauty fits into that definition. I

don’t think the two concepts, beauty and expression, are that difficult to

reconcile; but it is probably best to be as explicit as possible, especially

since we are dealing with a definition that has continued to mystify and elude

large parts of the critical and artistic population—at least since Modernism

began. In other papers I have said that

beauty exists, that it is a property of the object, and that it is very

important in art and life. Now I must

elaborate on those assertions, tying beauty to expression and thereby to

art. In several places Tolstoy

appears to lean toward the Kantian/Christian belief that beauty is the mistress

of the devil. That is, he implies that

he accepts Kant’s assertion that pleasure and duty are opposites—that the

morality of an act is determined by its unpleasantness. It has historically been difficult to

unravel exactly what Kant intended, but he certainly creates some sort of

dichotomy between pleasure and virtue.

A pleasant act cannot be virtuous and a virtuous act cannot be

pleasant. There are variant

interpretations of Kant, and I am not here to settle the question one way or

the other. It is enough in this context

to point out that an important line of thought in the history of morality has

argued in this way, and that this line includes many Christians and Kantians

(as well as Jews, Muslims and Buddhists).

So when Tolstoy denies that beauty is the central concept of art, it is

important to look at his intentions. Is

he, like me, simply subordinating the concept of beauty to the concept of

expression? Or is he arguing against

beauty along the Christian/Kantian lines, calling pleasure a temptation to

immorality? It is not easy to tell by

reading What is Art? Tolstoy

never addresses the question directly.

The best indication of his intentions is contained in his various

comments about nudity, sexuality, and eating.

In discussing the various natural appetites, his examples are all

negative examples. He points out that

you cannot judge the quality of food by asking how pleasant it is to the

appetite, and he gives the example of sweets and alcohol. He neglects to point out that people also

have very natural appetites for bananas, apples, pears, potatoes, rice, bread,

cheese, water, fish, meats, and many other things that are good for them. He also neglects to mention that sweets and

other similar things, eaten in moderation, are not really debilitating at all,

and that alcohol is an acquired taste.

Children don’t like alcohol or coffee or tea, unless it is milked and/or

sugared, in which case it can be argued that what they like is the milk or

sugar. Later they may get rid of some

or all of the milk and sugar, but then it can be argued that they are seeking

not taste but effect. They seek a

pleasant high, not a pleasant taste, though they may mistake one for the

other. In this way we habituate

children to the various vices, which would tend to damn our customs, not our

appetites. An analogous argument can be made about the sexual

appetite. Tolstoy implies that people’s

natural inclinations are for immorality: we desire bad sex as we desire bad

food. But I could argue that Hollywood

and pornography are the sugar-coating of something that people don’t have much

of a natural appetite for in the first place.

Like alcohol, adultery and weird sex are not initially that

appetizing. Most young teens are not

interested in orgies and wild experimentation.

But when these acts are glorified and glamorized they take on a false

sugar-coated appeal. Those pretty

people on TV and on the computer look to be experiencing something very

pleasant, in one way or another, and we are duped into pursuing it. Some get hooked; some no doubt really enjoy

it. But for many it becomes like a

drug. The surest proof of this is that

high levels of drugs usually accompany it.

The common answer to this is that drugs lower inhibitions. But a better answer is that the pleasure is

no longer in the touch, it is in the effect.

Sex like this is not about the intimacy or the touch, it is about the

high. Natural sex is like a good

healthy meal. It pleases the senses

directly and is salubrious in all ways.

Pornographic sex is like straight whiskey or cocaine. It tastes horrible. It does not actually appeal directly or

naturally to any of the five senses, but it achieves the high regardless, by a

sort of assault on the brain. Some may see my comments as

being just as anti-sensual as Tolstoy’s.

I may seem at first glance to be in just as great a backlash against

sensual or sexual freedom as the Victorians.

But there is a very great difference.

My explanation lays blame on customs, not on appetites. I have never found my appetites to be as

unserviceable to me as the Victorians, the Kantians, the Christians, the

Muslims, or the Buddhists found theirs to be.

When I found it necessary to resist “temptation”, it was not mainly the

temptation of my wandering appetites, it was the temptation of customs. I have never had any appetite for drugs,

alcohol, or sex with strangers, and so the customs have rarely affected

me. This puts me in a position to

contradict those such as Tolstoy when they begin preaching against the

perverted appetites of man. In attacking the pleasures and appetites, Tolstoy is

most orthodox. His belief in man’s

predisposition to do everything wrong goes back to the concept of original

sin. Both he and Kant take it as a

starting point. But this concept

contradicts my own personal experience, and none but the most indoctrinated can

ultimately accept that which contradicts personal experience. In short, I have found that appetites—though

not infallible as guides in the modern

world—are nonetheless more to be trusted to lead us where we need to go than

anyone or anything else. Certainly the

trustworthiness of natural appetites is greater than the trustworthiness of

customs, which are irrational and contradictory in the highest degree. Man, like all the other beasts, has an instinct for

self-preservation. Even more, he has an

instinct for health. The appetites are

initially tied to this instinct. The

appetites may become corrupted, but they are not originally

corrupted. Meaning that, in the life of

each person, they are not corrupted at birth.

The weakness of a person therefore consists not in an initial

corruption, but in a basic inability to resist corruption. This corruption presents itself in the form

of cultural customs. A desire for

alcohol doesn’t just naturally kick in at puberty, for instance. We are first offered alcohol at or near that

time in our lives, and most of us accept the offer. It is that simple. I

daresay most of us hated our first sips.

Some of us still have to milk or sugar our alcohol to get it down. Look around you at what people are

drinking. A desire for sex does kick in at puberty, of course, but

with most people a desire for intimacy is joined to it. Many will take one or the other if they

can’t get both, but most will agree that the ultimate search is for both. If this is true, it is hard to see how

anyone can blame the appetites. Even

those who choose to have sex without intimacy are not following bad appetites,

they are just making the best of a bad situation. They are not offered a full glass so they take half a glass. The logical thing to do would be to create

customs that make good situations more prevalent. This is not what our customs do, though. Just the opposite. Our customs outlaw or make impossible good situations and then

punish those who try ease their pain. Let me give an example to clarify my meaning. We all know that teens will never be

encouraged to have sex. But the one

thing that they are warned against even more strongly now is sex with

intimacy. Casual sex can be dealt with

by parents much more easily than real love.

Love gets in the way of schoolwork and may cause havoc with college

plans. Condoms solve many of the

problems of casual teen sex; teens falling in love cannot be solved so

easily. High, almost invisible walls

are therefore built against it. There

is no centralized program, no class, no religious movement, nothing that can be

pointed to directly. But the societal

pressure against teen love is as strong as any other pressure. It permeates everything. It is omnipresent, a basic assumption—it

does not even need to be put in writing.

This is the custom that seeds the sin. Casual sex is young people making the best

of a bad situation. Preaching against

beauty or pleasure or immorality is therefore completely beside the point. The appetites are not to blame. If teens, as naturally sexual creatures,

had the “moral” choice (sex with love and responsibility) on their short list

of choices, then we might blame them for not choosing it. But they don’t. That is the one choice they do not have. They are not allowed to get married or to

live together. Careers are now more important

than families or even soulmates, and so we have culturally subordinated sex and

love and families to college and jobs.

This subordination starts as soon as the teen hits puberty. Here are the choices for a teen as they stand now: 1)

marriage or cohabitation: unthinkable.

2) casual sex: frowned upon, though much less than in the past (as long

as it is with another teen). 3) no sex:

encouraged, but very sad. Is it any

wonder that people are so messed up sexually?

It is easy to see that 2 and 3 are both debilitating. Number 2 is debilitating for two

reasons. It is debilitating because it

is frowned upon and therefore more or less sordid; and it is debilitating

because it is sex without love, which numbs the heart. Number 3 is debilitating because it is a

sort of sexual anorexia. It is a

starving of the body for five or six years.

How can young people be expected to have a natural or healthy attitude

about something they have been repressing for almost half their lives? It is insane. And yet we are told that number 1 is the most debilitating

of the three. Why? It threatens college and career by creating

ties that are hard to break. The kids

won’t go to the best colleges possible if they are tied to eachother by real

feelings. They will want to compromise,

and one will have to follow the other.

It is also assumed that number 1 will lead to more teen pregnancy,

although this is debatable. It is sex

that makes babies, not love or cohabitation.

Yet parents wink at casual teen sex and go ballistic at teen love. Ignore the second part of that last paragraph for a moment,

though, and look hard at the first part again.

We don’t want kids compromising and following eachother to college, or

making decisions based on love. Could

anything be more sad or more telling than that? We bring our children up to have cold hearts and then have the

nerve to be shocked by the divorce rate. “What can we do?” say the fatalists. “Es muss sein. It must be.” And yet in the time of our grandparents it

was not like this. It is in the memory

of living people that the world was set up along different lines, lines that

took into account the sexuality of young people and the necessary priority of

union. Sexual unions and families were

not subordinated to colleges and careers.

It is not an insoluble problem or an eternal religious or moral

conundrum. It is a new problem, one

manufactured to suit the GNP and the corporations and the growth economy. That brings us back, albeit in

a long digression, to Tolstoy and Kant and the whole

Judeo/Christian/Muslim/Buddhist view of the senses, the appetites, pleasure,

and beauty. First of all, notice how

Modern art falls into the argument against pleasure and beauty. Most would expect Tolstoy and Modernism to

be on opposite sides. As I showed in my

paper on What is Art?, they are indeed foes in regard to many things,

most importantly the issue of decadence.

Modernism finds decadence both interesting and informative. It also finds decadence to be ultimately

progressive. Tolstoy finds intentional

decadence to be boring and regressive, and ultimately immoral. But Tolstoy and Modernism agree in very

basic ways on the question of beauty and pleasure: they are against it. Tolstoy’s orthodoxy is not hard to

understand, since it is part of his fundamental Christianity. Modernism’s orthodoxy on this issue may be

slightly more surprising. Modernism has

put into question a great many things, but it has accepted the first aesthetic

premise of Judeo-Christianity: the suspect nature of pleasure, beauty, and

appetite. This is where I part company with both Tolstoy and Modernism,

and it is where Tolstoy and Nietzsche are impossible to reconcile. Nietzsche was in basic agreement with

Tolstoy on the subject of decadence.

But Nietzsche’s view of pleasure and beauty came to him from the Greeks,

and Nietzsche had no quarrel with the appetites of healthy people. Nietzsche’s comments on sexuality are a mixed bag. Some of his commentary on women and sex is

purposely sensational, but his overall view of aesthetics—and the way it tied

to beauty and pleasure—was as un-Modern as it is possible to be. He was further from Modernism than even

Tolstoy, since an Amish sort of iconoclasm had no appeal for him. Or, to put it another way, Tolstoy and

Modernism are Apollonian; Nietzsche is Dionysian. Nietzsche, like the Greeks, was a sensualist. Moderns are not sensualists. In art, Modernism has managed the strange

feat of decadence without sensualism.

Modernism has promoted cultural deconstruction while avoiding pleasure

almost entirely. This is because beauty

was one of the things deconstructed first, and most fully. Nietzsche differed from Tolstoy

in another important way as well. He

would have found the glorification of the peasant mentality to be decadent in

itself, a cry for self-stultification—a pose to hide the weariness of age and

defeat. In The Anti-Christ, Nietzsche agreed with the

Buddhists that health was a primary goal of both life and of society. Power might be the ultimate goal, but power

was an outcome and adjunct of health.

He believed that healthy people were natural leaders, and that they had

very little need of society’s laws. A

person with healthy inner laws could and should disregard society’s laws, which

laws were at worst limiting and at best inefficient. The only rational use of customs and laws would be to make the

less healthy people more like the most healthy. This would be done by 1) not corrupting them, 2) helping them,

through education, to resist corruption.

Nietzsche didn’t spend much time promoting specific ways to do this (in

this book or any other) since he was not primarily interested in protecting

unhealthy people. He was primarily

interested in protecting healthy people from unhealthy customs and laws. The bulk of his argument was spent pointing

out ways that customs and laws had been perverted, so that they helped no

one. In fact, customs and laws had the

opposite effect: they did everything possible to negate the potential of

healthy people, and to make it impossible to differentiate the weak from the strong. One of the most successful ways to achieve

this perversion, beyond actual law making, was through the re-defining of words

and concepts. Nietzsche catalogued

hundreds of ways that words and concepts had been re-defined since antiquity in

order to camouflage the natural, healthy ideas that had originally

existed. We all know that he attacked

Christianity most violently for this.

The easiest example is the Biblical phrase “the meek shall inherit the

earth.” The ancient Greeks would have

found this phrase to be nonsense or sacrilege.

Who wanted the meek to inherit the earth? To the Greeks, this would have meant, “The losers shall win,”

which was itself like saying, “Darkness shall swallow the sun.” Most contemporary Christians accept the Biblical phrase

because they imagine that “meek” simply means “humble”. No one likes a braggart. But “meek” did not and does not mean simply

“humble”, as in “non-boastful”. After

all, a winner can be humble, if he wins without undue pride. In fact, humility implies someone who wins

occasionally, since a perennial loser would have no occasion for humility. It is hard to refrain from boasting when

you never have an occasion to boast.

No, meek also implies “deficient in spirit and courage” and “not strong”. See any dictionary. Do we want those who are deficient in

spirit and courage to inherit the earth?

If so, then we are on the way to achieving paradise. Go to any contemporary museum and you will see

that the meek have inherited art history.

Those with little or no artistic ability have found a way to redefine

the field in their own favor. It is

debatable whether the museum was the first institution to fall or the

last. But whether you believe cultural

history collapsed a hundred years ago, or whether you believe its final

collapse is still in the near future, it is certain that Nietzsche was

prescient. All this ties into Nietzsche’s aesthetics, and to the

argument at hand, since it is clear that Modernism, like Christianity, has

continued the decadent re-defining of words and concepts. The Moderns have often tried to claim

Nietzsche as a precursor, but this claim is even more preposterous than their

claim of Cezanne or Van Gogh. Nietzsche

is completely anti-Modern in that he would not see anything at all clever or

poignant in embracing decadence like Duchamp and Warhol and all the rest have

done. He also would not see anything

progressive in re-defining words as their opposites. Replacing art with anti-art, replacing depth with shallowness,

replacing earnestness with phoniness, replacing subtlety with brutality, and so

on. As an example, I saw in the New York Times today an

article by the art critic Holland Cotter, where he claimed that Rubens and

Warhol were “two peas in a pod”—“Everything Rubens did, Warhol did, and

more”. This sort of standing the truth

on its head would not amuse Nietzsche in the least. Cotter begins the article by saying, “Let us be devils and call

Andy Warhol the Rubens of American art.

Why not?” Well, how about this: because

it is not true. Nietzsche may have

been the anti-Christ, but this sort of tongue-in-cheek, swishy devilry would

have been for him beneath contempt.

Telling oily lies in order to make a master out of a slave is not

delicious, it is despicable. And finally, Nietzsche is anti-Modern in that he despised

egalite, especially an enforced egalite—a fascistic, centralized

propagandizing of false ideals. He was

already distressed about the fall from Mozart to Wagner, the loss of lightness

and subtlety and grace and melody. What

would he think of John Cage? He would

have already been distressed about the diminishment in spirit from Titian to

Gerome. What would he think of Tracey

Emin? For Nietzsche, Tracey Emin and

the other Saatchi and Turner Prize people would all be examples of the victory

of the slave mentality, nothing less.

The victory of vulgarity and resentment over beauty. My favorite quote of Nietzsche is

this one: “It is easier to be gigantic than to be beautiful.” Think of Pollock or Sol LeWitt or Chuck

Close. But one must remember that it is

also easier to be tiny than to be beautiful (Twombly or Johns). It is easier to be vulgar than to be beautiful

(Emin or Currin). It is easier to be

banal than to be beautiful (Rothko or Newman or Richter). It is easier to be annoying than to be

beautiful (Nauman or Warhol or Duchamp).

It is easier to be shocking than to be beautiful (Hirst or Bacon). It is easier to be ugly than to be beautiful

(Jenny Saville or Lucian Freud). And this brings us back to beauty. I have used pleasure and beauty almost interchangeably in the

argument above, since I began with Kant’s definition of beauty as that which

gives us pleasure [in my previous paper].

Tolstoy had accepted that definition, and, within limits, so will

I. Visual beauty gives us visual

pleasure, and this is the beauty and pleasure that are primary in

aesthetics. Music we may also accept as

aesthetically beautiful, since the sort of pleasure we receive is one that is

easily tied to the commonsense definition of art. We call music art, and the kind of pleasure we receive from

music is similar to the pleasure we receive from looking at a beautiful picture

or a beautiful scene or a beautiful person.

A poem may be both visual and musical, as well as literary. Literature is an art because it generates a

complex feeling, usually many complex feelings. Dance is an art that mixes visual and musical beauties. Taste, touch and smell are not commonly given to art, and

I agree with this distinction. It may

be because these senses are more primitive.

Their impressions reside in deeper, older parts of the brain. It may be because the causes of these

impressions are not as complex, not as skillfully manufactured, not as

permanent, or for other reasons.

Preparing fine food, giving a skillful massage, or inventing a perfume

may be artistic to some degree, but no semi-permanent artifact is created. More importantly, no specific emotion is

revealed. No complex feeling, beyond

“Ahhh!” is generated. Fine wine and

food does not cause the imagination to turn on and begin functioning in

specific ways. Art does. Art creates emotions and feelings through

the brain, not just through the nerve endings.

Even a piece without words or images, like a sonata, functions at a much

higher level of complexity than a meal or a massage. In fact, brain imaging reveals this. Art lights up multiple areas, not just a pleasure center. Art massages the entire neo-cortex as well

as large parts of the inner brain. Food

and perfumes and backrubs don’t do this.

Of course this is no argument against food, nice smells,

backrubs, or sex, none of which I consider artistic, but all of which I

consider both pleasant and very important.

Sex calls up complex feelings and emotions, but it does it directly,

without the creation of an artifact or a signifier of any kind. It is the human body that is the signifier,

and we may not take credit for the creation of that signifier. Sex may be partly artistic, in that I may

take some credit for what I do with my body in bed. No doubt there are sexual geniuses just as there are musical and

literary geniuses. But I find it more

useful to limit definitions in commonsense ways, rather than spread them thin

across all possible actions. Calling

sex art does not benefit anyone, sexual geniuses least of all (who need no

favors from critics or etymologists). I have covered a lot of ground

here, but I still haven’t tied beauty to art.

In the previous paper I said that art was not required to be beautiful,

so there is no necessary tie at all.

But if beauty is not a necessary ingredient, it is an important

ingredient. The artist uses beauty just

like nature uses beauty: as a propellant.

Sensual pleasure is an irresistible draw. Beautiful colors, lines, melodies and the rest attract us

precisely like flowers attract bees.

Beauty is therefore a tool.

Like any other tool, it can be used for good or for ill, although it is

neither in itself. Venus flycatchers

draw insects to their doom with patterns and odors, just as Hollywood draws an

audience to its intellectual doom with Orlando Bloom and Keira Knightley. This does not mean that beauty and pleasure are Sirens,

however. Our appetite for all kinds of

beauty is not a leading into temptation.

Beauty is a force of nature like gravity, and no one would think to call

gravity a temptation or a Siren.

Gravity causes life to adhere to the earth—and also causes planes to

crash. Beauty attracts us to eachother,

causes unions, causes children, causes smiles, causes health and

satisfaction. It can also be a lure to

propaganda, dishonesty, heartache, pain, financial ruin, and empty or malicious

art. If a criminal used a giant magnet to steal precious metals or

to down airplanes, we would not blame magnetism. Blaming beauty, pleasure and appetite for human corruption is no

more logical than giving magnetism criminal intent. Magnetism has only criminal potential. But everything has criminal potential. A criminal could use real messages from

heaven to dupe people into various corruptions, and it is possible that some

criminal has done just that. Criminals

have certainly used fake messages from heaven to that purpose. None of the fault lies with beauty, pleasure or

appetite. Fault lies with its use as a

tool, and ultimately with the user of the tool. Corrupted appetites have always been a big business, from the

beginning of history. Alcohol, drugs,

bad food, pornography, prostitution, advertising, propaganda, and fake art are

all related. They are all forms of

human bonsai: the forcing of natural

healthy appetites into weird and unnatural shapes. Beauty does not deserve any of

the abuse she has taken in the 20th century. Likewise, the appetites do not deserve the

historical abuse they have suffered from all the major religions. What is needed is not less appetite, but

less corrupting influence and more strength to resist corruption. In societies with little corrupting

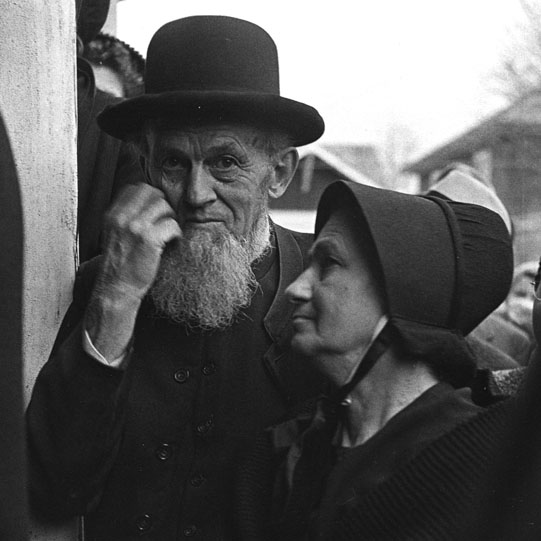

influence (tribal cultures, and also the Mennonites and Amish) the appetites do

not cause nearly as many problems. Notice that I am now praising the Amish, whereas above I

have been attacking them. The Amish and

Mennonites are an instructive example in more ways than one. They have successfully limited corrupting

influence on the appetites, and they have limited art as one of these

corrupting influences. In limiting corrupting

influences, they are absolutely correct.

In limiting art by category, I think they are mistaken. Their taboo on images and decoration comes

primarily from the Old Testament ban on graven images and other such

rules. But this Biblical ban had little

to do with beauty or pleasure. It

concerned a jealous God who did not want to compete with golden calves and

other pagan refuse. Of course

Judeo-Christianity has always been wary of pleasures, sexual and otherwise, and

the iconoclasts have, from the beginning, interpreted the ban on graven images

as another warning against the snake in the garden, whether it was intended

that way or not. According to my argument above, the Amish and other

iconoclasts have needlessly given up natural pleasures. What was always most needful was not

avoiding pleasures or appetites, but avoiding corruption of those

appetites. Beauty and pleasure in

service of the good is good; beauty and pleasure in service of the bad is

bad. A culture or community needs to

avoid only the latter. In some ways

this is understood, I think, for the Amish have never forbidden themselves

enjoyment of good sex and food. As

regards art, they are not as enlightened.

They have not forbidden all sex and food, since this would be absurd. And yet they think they must forbid all

art. How can art be more dangerous

than food or sex? Plato apparently thought that art was more dangerous

than food or sex. Tolstoy also flirts

with this possibility. It is a

flattering idea to an artist, but I cannot accept it. It is much easier to explain it this way, I think: people cannot live without food or sex. They can live without art. In a cultural pinch, they can make do with

natural beauty—the mountains and trees and flowers around them, as well as

their own physical beauty. The most

creative among them no doubt feel cramped, but what is that feeling compared to

the health of the community? In this way the Amish and Platonic ban on art is a signal to

us of something more profound. The

Amish and the Platonists ban art because it can be banned. If sex could be banned, no doubt it would

be. The easiest way to prevent

corruption is to prevent all action. If

you cannot act, you cannot sin. An

entire area of existence can be addressed with one law. Very efficient. But this method of making laws and customs is nihilism. And we are back to Nietzsche (I

am creating some weird, accidental hermeneutic circles here—now this is jouissance!). By nihilist Nietzsche did not mean someone

who is a non-believer, someone who is an atheist or agnostic. Nor did he mean an anarchist, a malcontent,

a political revolutionary, a terrorist, a materialist, an idealist, or anything

else like this. A nihilist was for him

not a denier of the Christian God, the state, the party, or the president. A nihilist was a denier of life. Plato, Tolstoy, and the Amish would all be

exhibiting nihilism, since they were denying the natural exercise of

appetite. Nihilism is present wherever,

in order to combat decadence, corruption, badness, or evil, a rule is fashioned

that outlaws both good and evil. It is

the outlawing of a set of actions by category, without regard to moral outcome. If all art is outlawed, then even art that

makes people more moral is lost. This

is nihilistic, since it forbids action for no good reason. Life is action.

The appetites are all in place to promote action, movement, change,

continuous creation. Any restriction

on this creation must be suspect. Some

restriction may be acceptable, if good arguments can be made for it. But blanket restrictions, restrictions by

category, preclude this possibility. A

people who trusted and adored their gods or nature would feel compelled to give

a full explanation of any restriction of appetites given them by those gods or

by nature. Restriction without full

account would, for such a people, be the ultimate sacrilege. The sacrilege of nihilism. Stopping life to suit easy or lazy

legislation. Refusing to take life on a

case-by-case basis because it is wearisome to do so. This sort of nihilism is closely related to hubris, since

only a self-satisfied person or people would imagine themselves within their

rights to restrict life or nature without a full account to her. All laws that do not take into account

individual circumstance are nihilistic and hubristic, since they restrict

action as a category and do so mainly as a means of legislative efficiency. The most nihilistic cultures and religions

are those that most restrict by category without a full account. This is why Nietzsche attacked Christianity

with such vehemence. On a whole host of

issues, Christianity has recommended inaction or abstinence. To fight evil, all the world religions have

restricted both good and evil. This is

why Nietzsche called Buddhism nihilistic as well. To combat spiritual pain, it restricted all action. This calmness was certainly salutary: it

worked. But for Nietzsche it was

ultimately sacrilegious, for the cost of this philosophy was life itself. To diminish pain, both pain and pleasure

were restricted. To diminish sin, both

good action and bad action were restricted.

But no specific sin is as harmful to the individual or the community as

the primary sin of categorical inaction.

To put it another way, a law or custom that prevents good

people from doing good things cannot be justified because it also prevents bad

people from doing bad things. It is

more important to do good than not to do bad.

We are here to do things, not to refrain from doing things. We are here to live, not to refrain from

living. This should be the first

principle of any legislation, and therefore action should always trump

inaction. To put it one more way, it is

better to have both good and evil than to have neither. A person who disagrees with this last sentence is a

nihilist, by Nietzsche’s definition, and mine.

Plato and Tolstoy and the Amish all exhibit nihilism when they ban, or

threaten to ban, art by category. The

major world religions all exhibit nihilism when they promote abstinence or

chastity or any other categorical suppression of the natural appetites. All the governments of history have

exhibited nihilism when they have passed laws that restricted action by

category, without regard for individual circumstance. Since all governments have done this, and since almost all laws

exclude exceptions, all laws and governments have been nihilistic. Logical laws

would address not categories of actions, but specific actions, since only

specific actions are corrupted, evil, sinful, illicit, or harmful. Failure to address specific actions is a

religious failure, since it concerns our relationship to life itself. That is, no matter what your religious

affiliation, you have some relationship to life. Even atheists have some philosophy of life, some general stance

toward existence. Therefore this legal,

logical, and aesthetic failure concerns everyone equally, not just artists, or

legislators, or overtly religious people.

To the extent that we fail to resist nihilism, we are complicit in

it. I must hit one final topic

before I close. Tolstoy used his book What

is Art? to encourage the highest sort of artistic expression. In a different way, I have done so here

too. That is all fine and good, but it

leaves open the question of the status of “pretty pictures.” It is easy for Tolstoy and me to attack art

that we find really objectionable and to praise art is that we find great. But where does that leave “decorative”

art? Where does that leave harmless

paintings of flowers and cows and donkeys and lakes and mountains and so

on? Some will think that we have set

the bar so high that no one can reach it.

If Tolstoy complained of Michelangelo and Beethoven, how is there any

hope for us mortals? If Tolstoy wants

inspiring, expressive, emotional art, then it is not clear that anyone really

achieves that. What do we make of

Sargent or Bouguereau? They weren’t

corrupting, but were they expressive?

What does this “expressive” entail, anyway? Must there be some uplifting moral story implied? Does one have to imagine the brotherhood of

man with a tear in his eye every time one looks at art? As I have said before, I think Tolstoy’s exhortations were mostly

well-meaning and to the point. However,

I think it might be easy to finish his extended sermon with a bit too jaded an

outlook. The same could be said of my

extended sermons, I suppose. One may

get the feeling that nothing short of new Sistine Chapels will impress us. At least in my case, this is not true. I don’t feel guilty about my own portfolio

after reading Tolstoy, and if I don’t I could hardly use Tolstoy to critique

Sargent or Bouguereau or anyone else. I

personally find loads of expression in both Sargent and Bouguereau, although

others who go in looking for specific kinds of expression will not find it

there. I think straightforward

portraits can be among the most expressive things. A head by Van Dyck has buckets of emotion in it, although it is

not emotion that is easy to put into words.

It is not Modern emotion, it is not literary emotion, it is not

religious fervor, it does not generate ideas, it is not political emotion. But those who have eyes know what I

mean. It is the nameless emotion of

reading another person’s character from his or her face and expression. More than this, it is the sympathy of the

artist draped over this character like a second soul. The portrait is a tripartite communion, with the viewer

completing the number. Possibly there

is no stronger feeling in art or in life.

When you look in the eye of your lover during the act, this is what you

feel. Only in art or sex are you

allowed that stare. To a lesser extent, you obtain that emotion from all

successful objective art. It seems

strange to suggest that you look at a cow or a cloud or mountain like a lover,

but there it is. The stare of a lover

is allowed, it is encouraged. Beauty is

no longer forbidden, no longer suspect.

You can stare and think whatever you like: the critics will not know the

difference. You can tell them what they

want to hear and make your exit. I am not saying that every painting of a cow is great art,

or deserves my defense. But a great

painting of a cow is an artistic possibility.

Van Gogh looked at the night sky, at his own shoes, at sunflowers, like

a lover. This attitude made it art, not

the subject. Subject matter is

important, but only because you must genuinely find your obsessions. Van Gogh did not manufacture a love of the

night sky, he actually felt it. He knew

his lovers, and he knew how to love them. So yes, in a sense one does imagine the brotherhood of man

with a tear in his eye everytime one looks at art. My explanation has not ended up as far away from Tolstoy as I had

thought it would. But the brotherhood

must be extended to all objects, including cows, shoes, stars, and rocks. This is why no subject should be forbidden by

category. There is no category of kitsch,

no subject that is impossible to paint.

To the artist all is allowed.

Those who would forbid or denigrate artistic subjects by category are

also nihilists. Notice that I have

completed one last circle, and now I will quit. If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction. |